Free video consultation | Tuesday 24th February

The next session will be on

Tuesday 24th February 2026

With Dr. Martin Wiese

Book a free video consultation with one of our surgeons, to discuss your symptoms, explore treatment options, and receive expert advice, all from the comfort of your home.

The Shouldice repair explained

The Shouldice technique is an advanced suturing method for repairing inguinal hernias, focusing on reinforcing the weakened area in your groin using sutures and your own tissues. Amongst the hernia repair techniques we employ, the Shouldice method is the most scientifically validated.

Starting your repair

Following the administration of either a general or local anaesthetic, we start the inguinal hernia repair by making a small 3 to 5cm incision in the lower abdominal area. Throughout the procedure, a dedicated anaesthetist is on hand to ensure your comfort and well-being.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

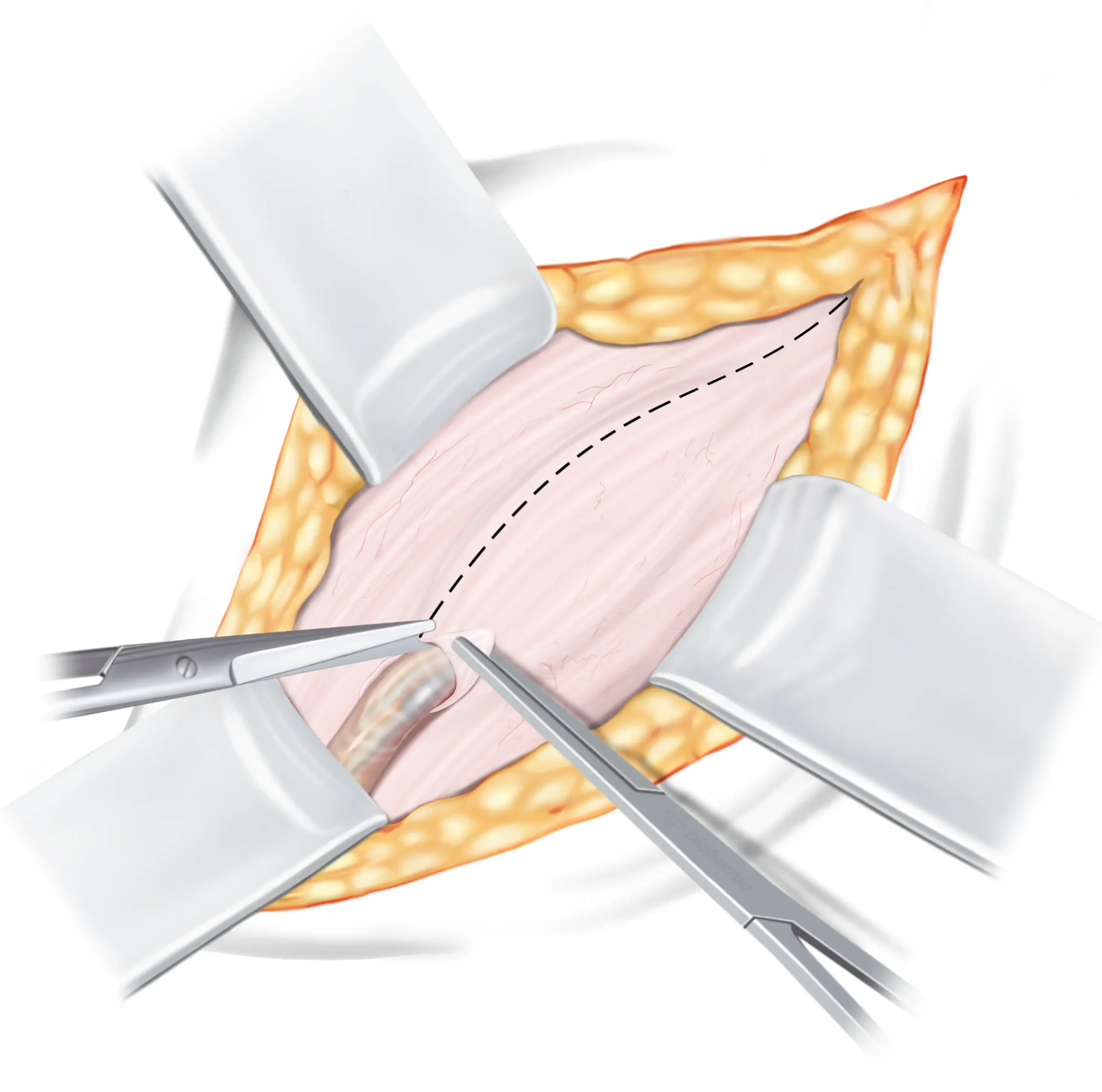

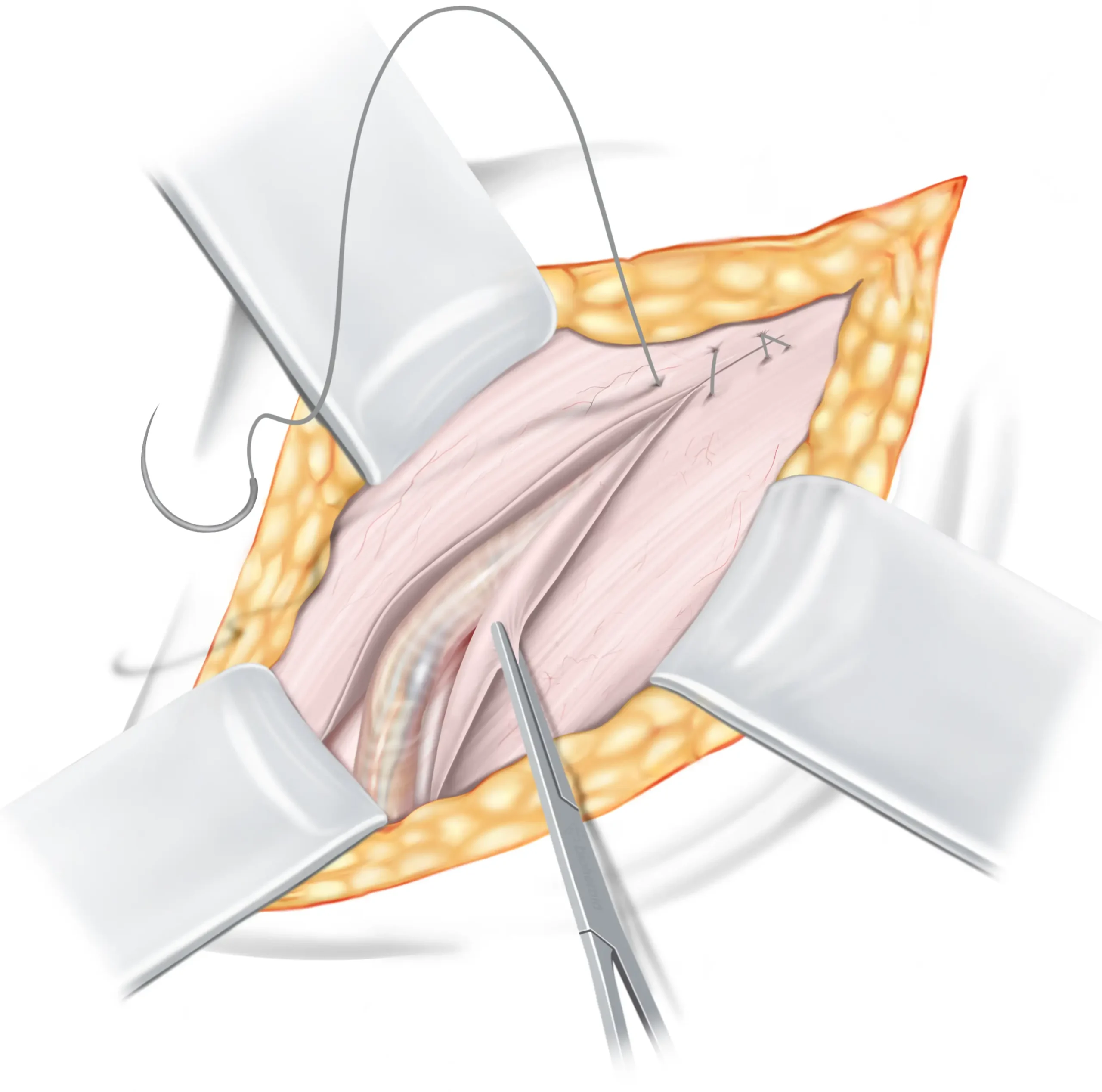

Opening the inguinal canal

The first tissue we encounter is the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle ↓, which forms the roof of the inguinal canal ↓ . To gain access to the inguinal canal for the repair, we need to open this tissue. It is important to note that opening the external oblique aponeurosis (EOA) does not have any negative impact on its functionality, as it will be closed again during the final step of the operation. Once opened, the spermatic cord ↓ is safely pulled to the side and the two flaps of the external oblique aponeurosis are carefully retracted as they will be utilised later in the repair process.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The external oblique aponeurosis is incised from the superficial inguinal ring past the deep inguinal ring. After opening, the upper leaf of external oblique is slightly elevated and undermined with a finger, to free it from the underlying internal oblique muscle.

Hernia sac management

Inguinal hernias can manifest in two ways: as an indirect hernia sac or a direct hernia sac. While both types of hernias involve protrusion of intra-abdominal tissue through a weak spot in the groin, there are distinct differences between the two. For the Shouldice repair however, it is not important which of the two types of hernias you have, as the technique fixes both at the same time. If you want to understand the difference between the two types of hernias, please read more about it in our FAQ, at the bottom of this page ↓

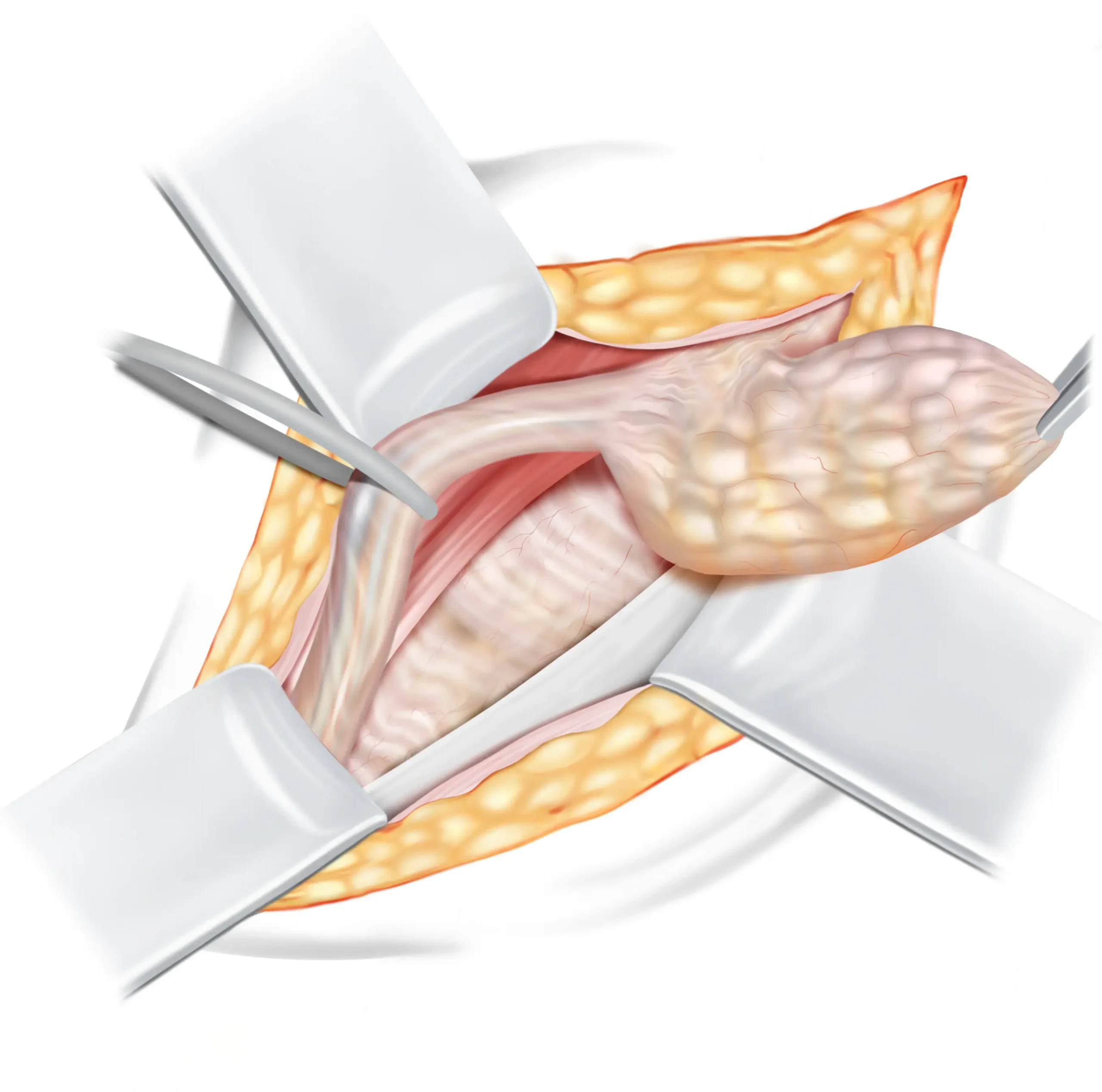

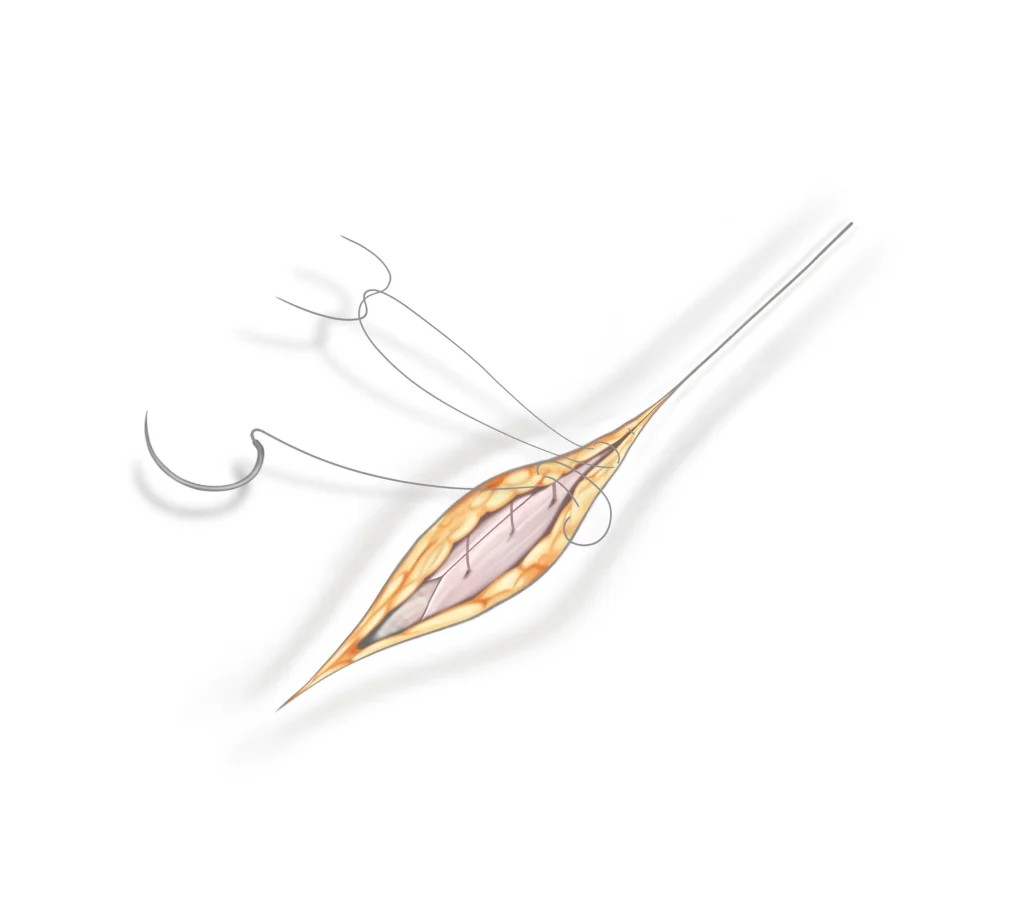

Indirect hernia sac

An indirect hernia is a bulge that emerges from the internal ring, alongside the spermatic cord . During the repair, this bulge or ‘sac’ ↓ has to be pushed back into its proper place. The sac may be opened to check its contents and then, the sac is tied off close to the internal ring to prevent it from bulging out again. After that, the extra or unnecessary part of the sac may be removed to ensure a tidy repair.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The sac must be dissected up to the opening in the transversalis fascia. For indirect hernias, this entails a full exposure of the deep inguinal ring. All around the deep ring, the hernia sac should be meticulously dissected and detached from any attachment to the transversalis fascia. The sac can then be treated in various ways. At the deep ring, it might be twisted, transfixed, and ligated. The protruding end is then removed.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Indirect hernia sac

(containing fat or bowel)

Inguinal ligament

Internal oblique muscle

Transversalis fascia

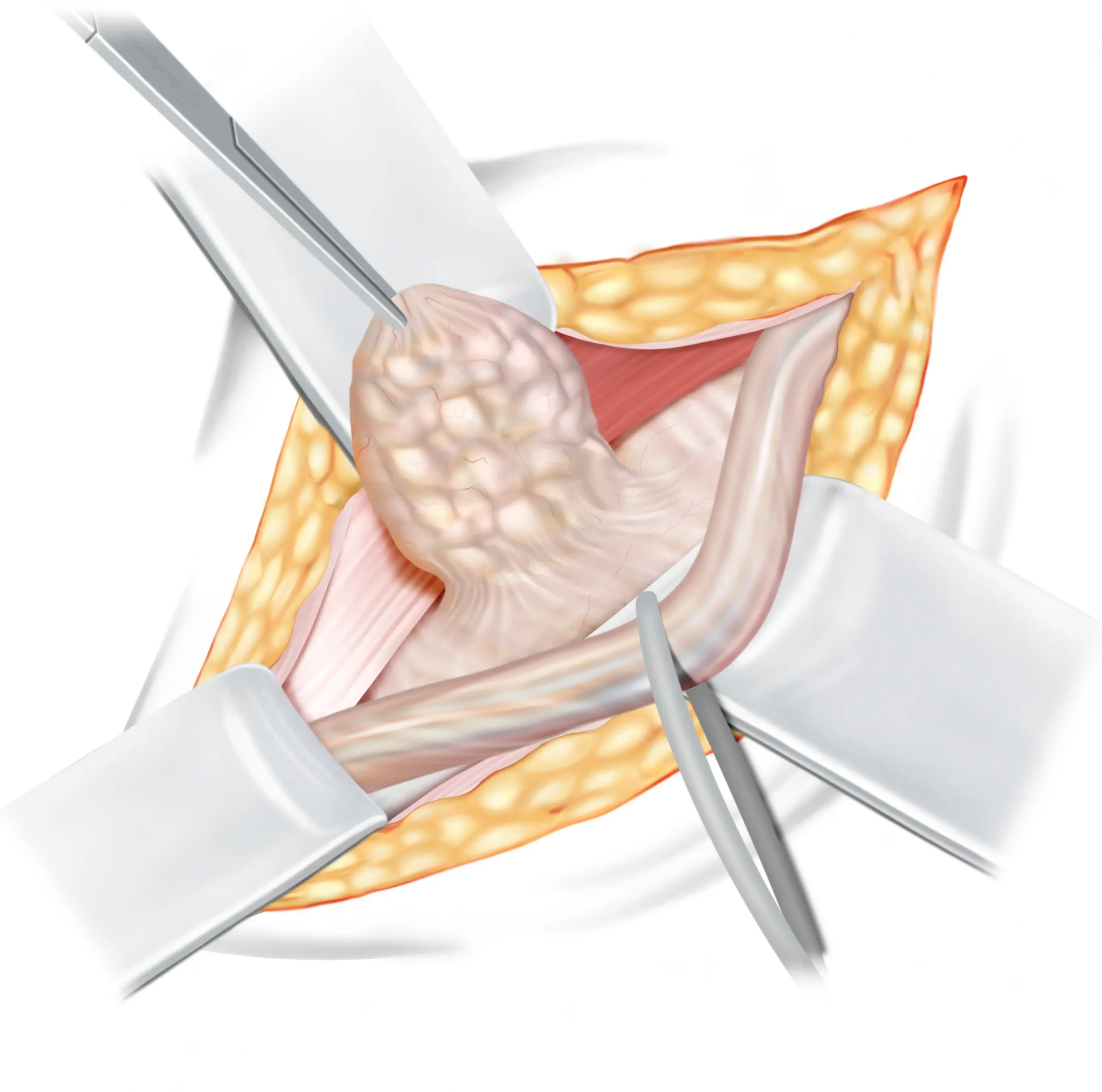

Direct hernia sac

A direct hernia is a bulge that emerges directly through a weakened inguinal floor. In a direct hernia, the hernia sac ↓ typically doesn’t need to be opened. If the sac is large in size, it should be reduced, and the base secured with a purse-string suture.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

Upon reaching the internal ring, the suture reverses to form the second line. This line moves towards the pubic crest, integrating the loose edge of the triple layer to the inguinal ligament. Close to the pubic crest, the suture connects and secures with the earlier left tail end.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Direct hernia sac

(containing fat or bowel)

Inguinal ligament

Internal oblique muscle

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Upper flap of external

oblique aponeurosis (EOA)

Transversalis fascia

Internal oblique muscle

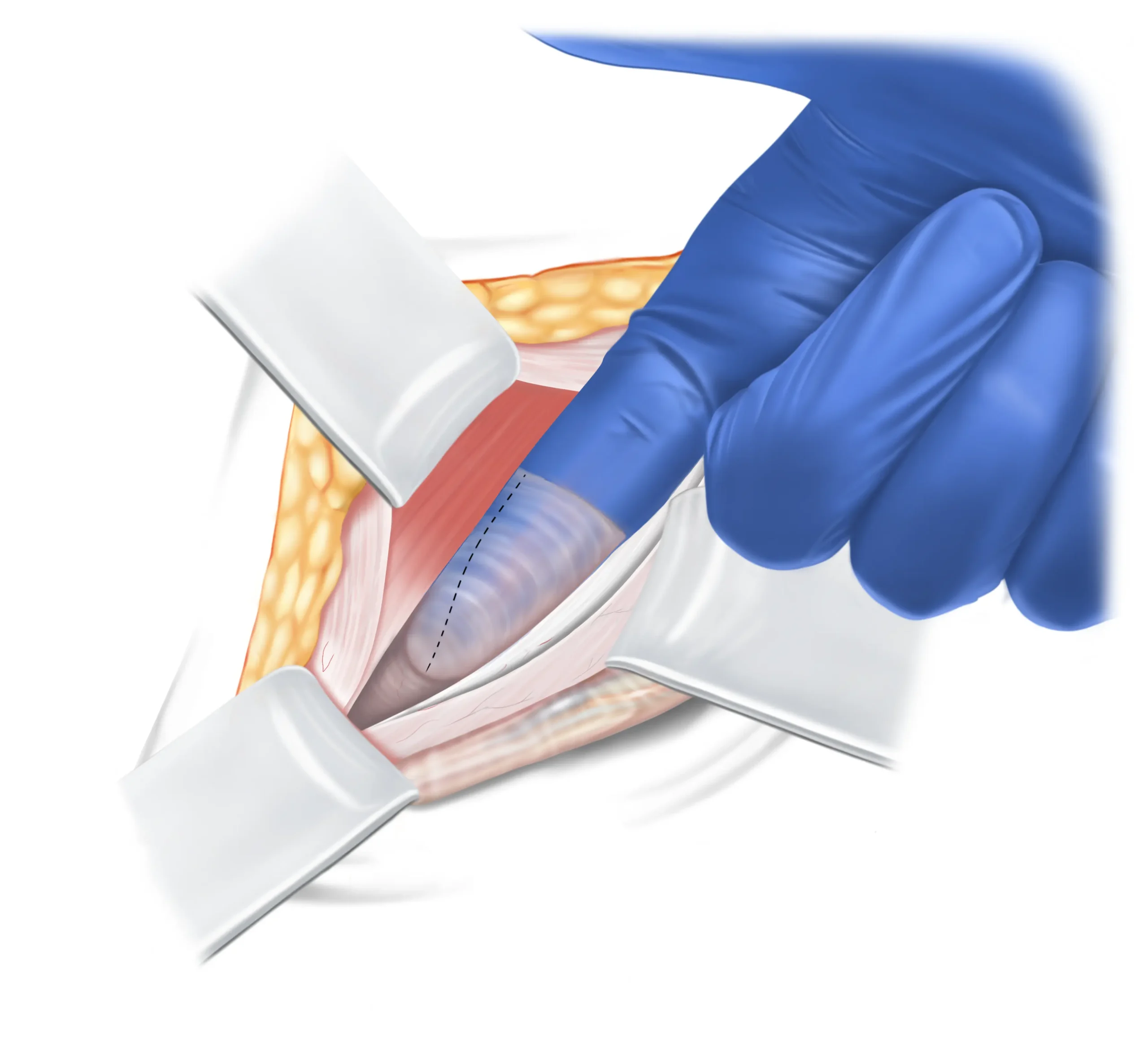

Testing the strength of your tissue

Before the actual repair, the quality of the tissue needed in the repair is assessed by feeling it with a finger through the opened hernia sac. After testing the strength of the tissue, it is divided, as it will be used in the next steps of the Shouldice repair.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

Prior to the repair, the quality of the transversalis fascia is assessed either by palpation through the opened hernia sac or via the deep inguinal ring. Once evaluated, the transversalis fascia is divided for incorporation into the Shouldice repair sutures.

Shouldice repair sutures

The Shouldice repair consists of a four-layered suturing technique, overlapping layers of tissues in your groin, to create a natural and durable barrier and effectively preventing the recurrence of both direct and indirect hernias.

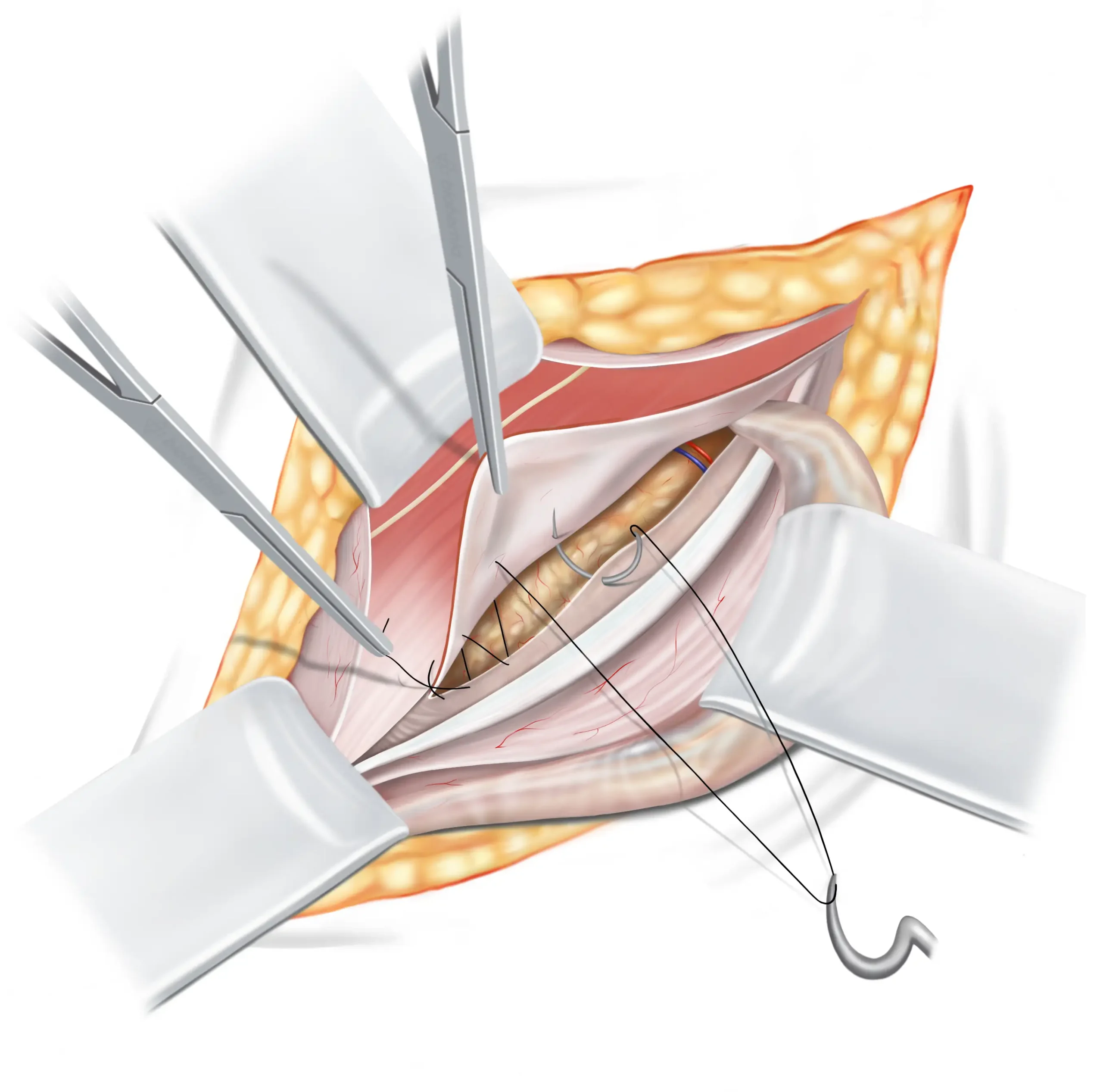

First suture line

The first suture is secured, leaving a bit of it extended. This extended part will later connect with the second suture line. As this suture travels sideways, it joins three layers of tissues and muscles to the lower flap of the transversalis fascia. The suture then proceeds to the internal ring.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The suture is tied off, leaving a long tail to merge with the returning suture from the second line. As the initial suture line moves laterally, it encompasses the triple layer from the medial side over to the iliopubic tract on the lateral side. A section, roughly 1 cm in width, of the medial flap is crafted to dangle freely. About halfway towards the internal ring, the edge of the rectus becomes unavailable and is left out from the continuous suture, which then carries on to the internal ring.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Inguinal ligament

Iliohypogastric nerve

Internal oblique muscle

Extraperitoneal fat

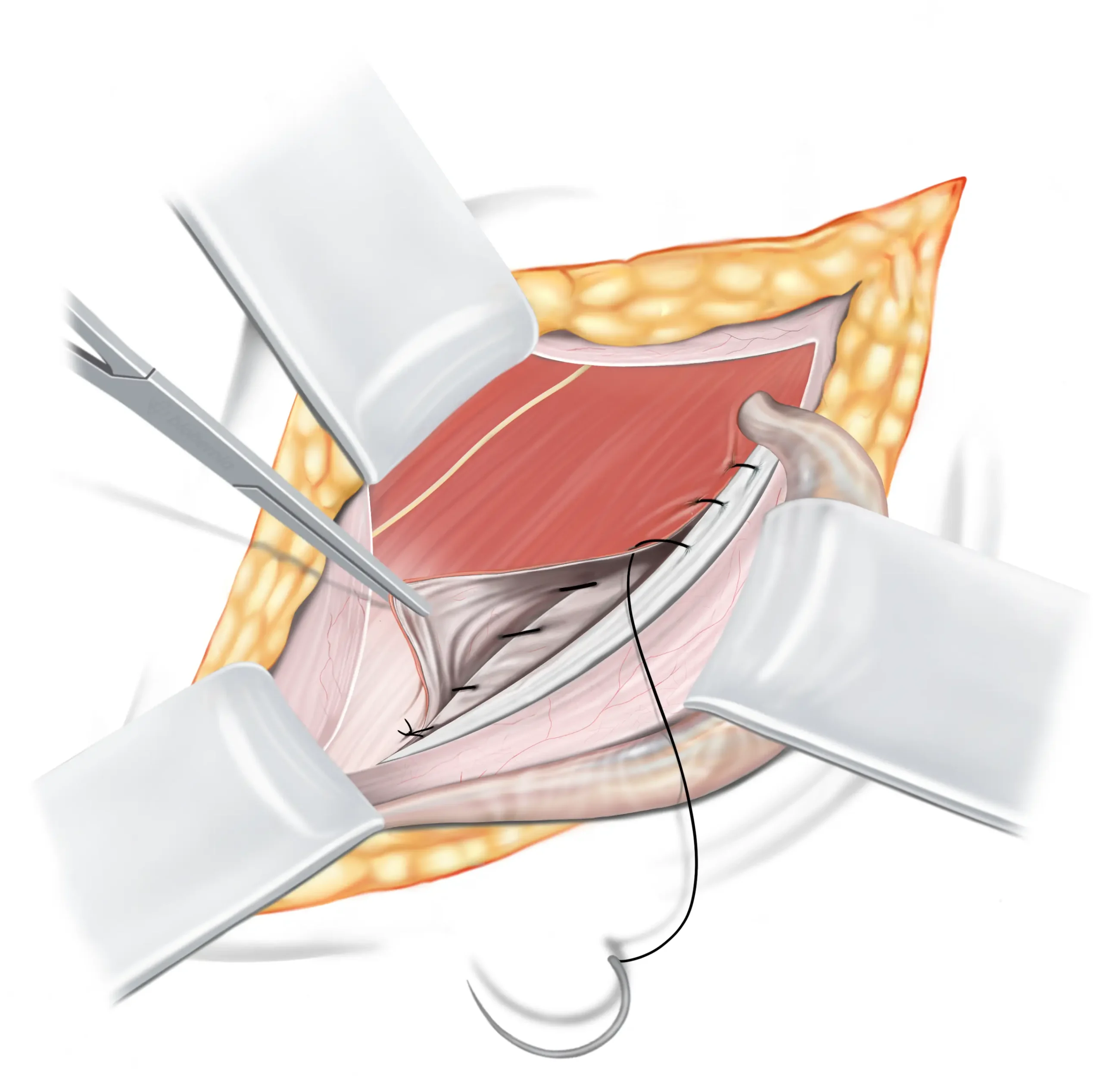

Second suture line

At the internal ring the suture line reverses, attaching a hanging part of the three layers of tissue to the inguinal ligament. When it reaches the beginning of the first suture line, it is secured to the tail of the first suture, that we left earlier.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

Upon reaching the internal ring, the suture reverses to form the second line. This line moves towards the pubic crest, integrating the loose edge of the triple layer to the inguinal ligament. Close to the pubic crest, the suture connects and secures with the earlier left tail end.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Iliohypogastric nerve

Inguinal ligament

Internal oblique muscle

Flap of three layers:

1. Internal oblique

2. Transversus abdominis

3. Transversalis fascia

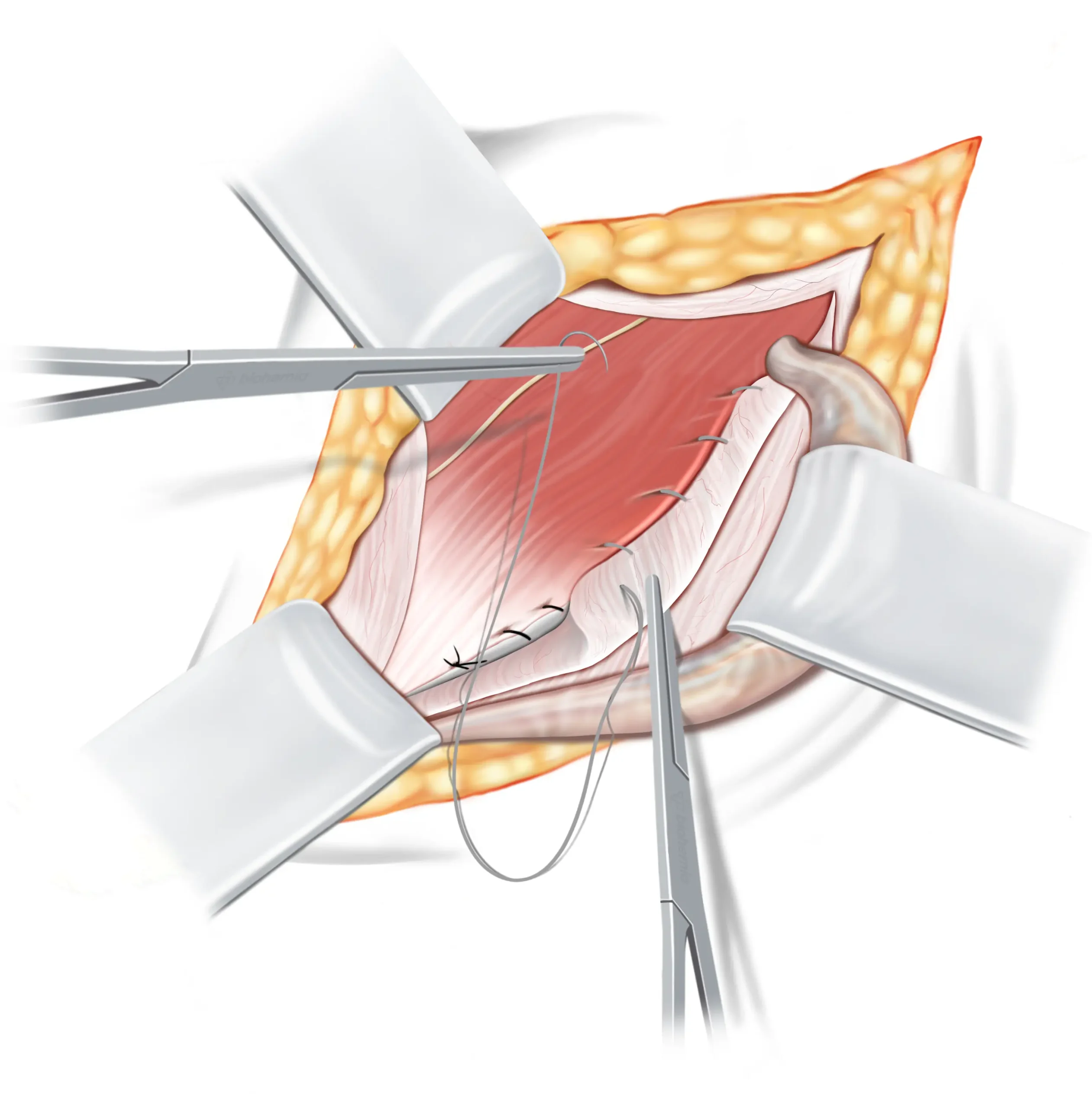

Third suture line

We’ll proceed to use a second suture now, which will be used for both the third and fourth row. For this step we use a resorbable suture ↓. It starts near the internal ring, picking up the middle part of our three-layered flap, then it shifts to include a bit of the EOA. It runs close to our previous suture row but closer to the surface, effectively forming a secondary inguinal ligament.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

We’ll now proceed with the second suture, which will be used for both the third and fourth lines, for which we use a resorbable suture. Starting from the internal ring, the third line first engages with the medial side of the triple layer, then shifts to integrate the inner layer of the EOA, running adjacent to the second line but at a more surface level, thus creating a sort of second inguinal ligament.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Retracted flap external

oblique aponeurosis

Internal oblique muscle

Iliohypogastric nerve

Upper flap of external

oblique aponeurosis

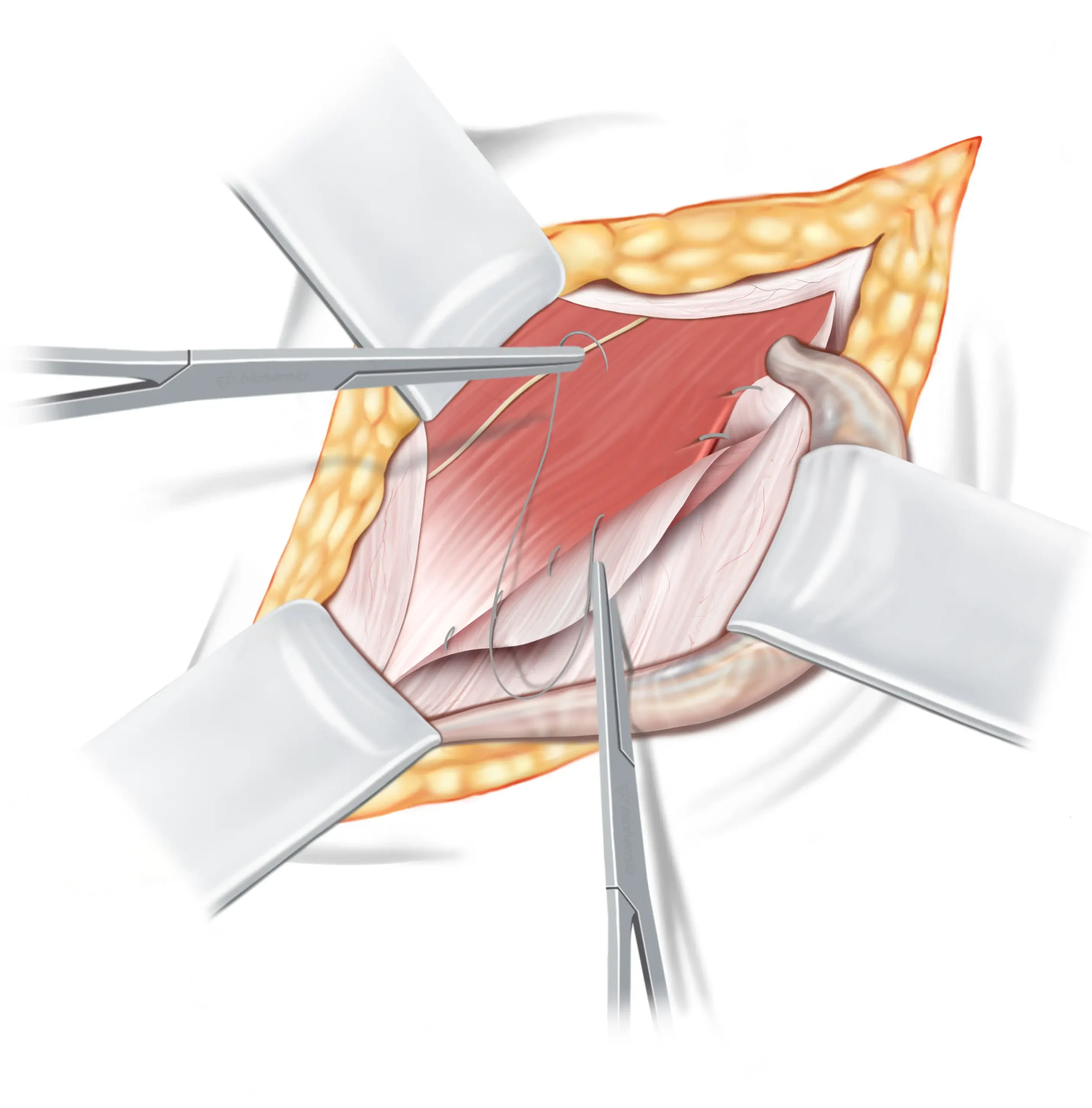

Fourth suture line

The suture line then reverses back towards the inguinal ring, and ends by securely tying both ends of the suture line together.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

Upon reaching the pubic crest, the fourth line proceeds back towards the internal ring, seamlessly merging the triple layer with the interior side of the EOA, as though creating another inguinal ligament. Concluding at the internal ring, both ends of the sutures are securely tied together.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Iliohypogastric nerve

Internal oblique muscle

Retracted flap external

oblique aponeurosis

Upper flap external

oblique aponeurosis

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

Finalising your repair

The spermatic cord is carefully returned to its natural position, and the inguinal canal is closed by bringing together the fascia of the external oblique muscle and securely suturing it with resorbable sutures.

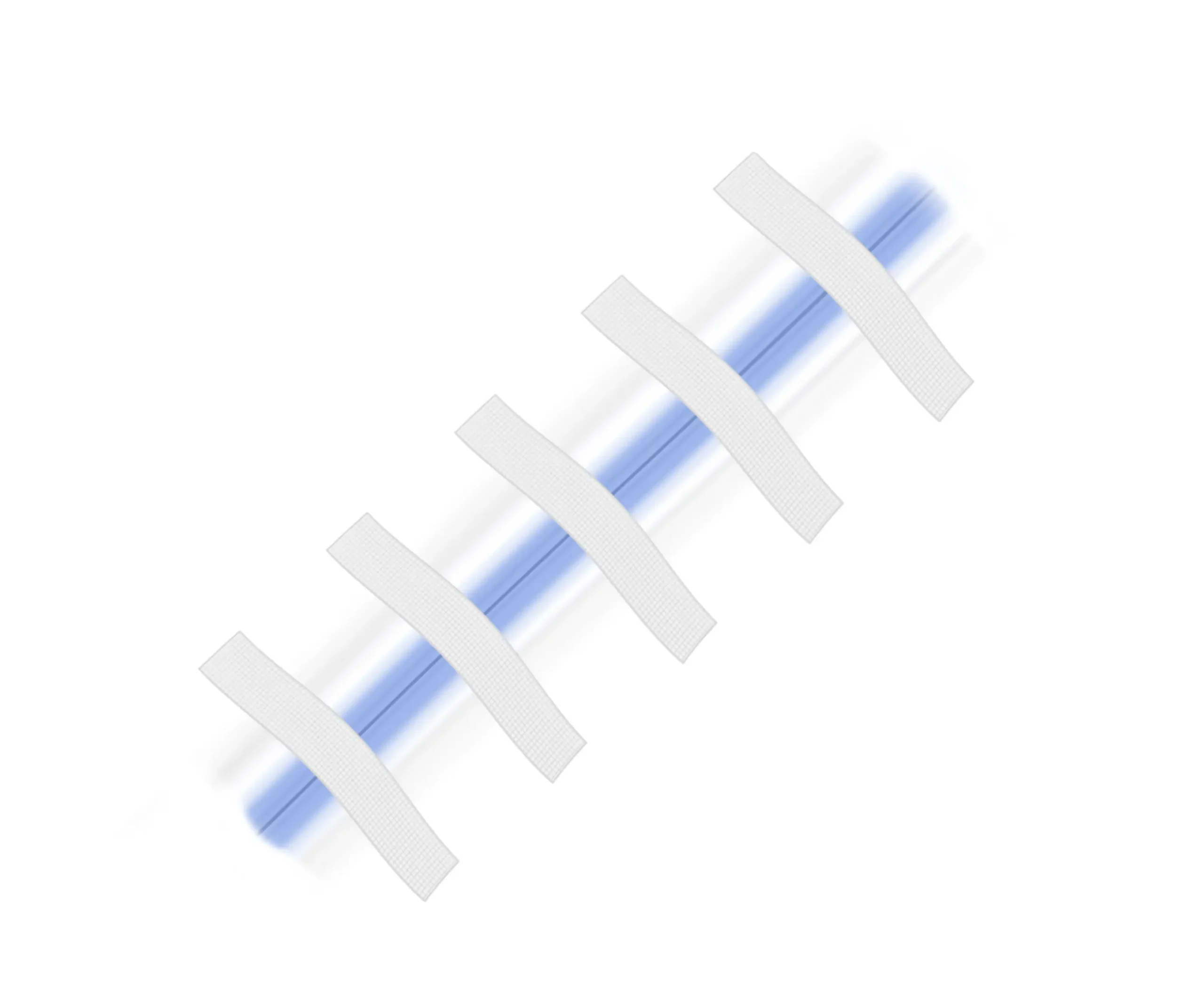

Closing the skin

After the procedure, the incision is closed using sutures that the body naturally absorbs. Therefore, there is no need for you to return for suture removal, as these sutures dissolve on their own. Local anaesthetics will also be applied, which could make the area look somewhat swollen after the operation, but this is a typical response and helps reduce pain after the operation.

Wound care

In the final steps, medical glue and Steri-Strips are applied to your wound. These strips aid in holding the wound’s edges together, minimising potential scarring during the healing process. You can safely remove the strips after one week.

DISCLAIMER

The illustrations displayed on this page have been adjusted in size (some enlarged and others reduced), to enhance understanding. They are intended to provide a simplified explanation of the operation technique and do not accurately portray the complex nature of human anatomy, nor do they convey the intricate challenges encountered during actual surgical procedures. Within the human body, everything is interlinked, making the identification of tissues, nerves, and blood vessels more challenging than what is suggested by the illustrations. Consequently, considerable experience and surgical skill are essential to accurately and effectively perform the operation technique illustrated.

Frequently asked questions

1. How was the Shouldice technique developed?

During the Second World War, Canadian surgeon Dr. Edward Earle Shouldice (1890-1965) developed the technique to assist young men whose inguinal hernias prevented them from enlisting in the military. His innovative method significantly reduced recurrence rates and sped up recovery times. Recognising the potential of his technique, Dr. Shouldice opened the Shouldice Clinic in 1945, in Toronto, Canada. Thereafter, the Shouldice technique grew in popularity and became the gold standard for non-mesh hernia repairs—a standard it retains to this day. Amongst the hernia repair techniques we employ, the Shouldice method is the most scientifically validated.

2. What makes the Shouldice repair different from other hernia treatments?

The Shouldice repair is unique primarily because it’s a non-mesh technique. Unlike other methods that use synthetic meshes, the Shouldice repair involves a natural, tissue-based approach. This method meticulously reinforces the abdominal wall using a series of small, precise sutures, reducing the risk of complications associated with meshes, such as infection or mesh rejection. Among non-mesh repair techniques, the Shouldice repair stands out for being the most scientifically validated. Extensive scientific evidence demonstrates that, when performed by experienced surgeons, the Shouldice repair provides outcomes better than mesh repairs.

3. Is the Shouldice repair suitable for all types of hernias?

While the Shouldice repair is highly effective for many hernia types, especially inguinal hernias, its suitability varies based on individual factors like hernia size and location. We recommend that potential patients complete our assessment form to determine if they meet the criteria for the Shouldice repair. This step helps ensure that each patient receives the most appropriate and personalised treatment plan.

4. Are any nerves cut during the operation?

In the inguinal area, there are three nerves: the ilioinguinal nerve, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, and the iliohypogastric nerve. During our inguinal hernia operations, none of these nerves are cut. We take the utmost care to preserve these nerves, ensuring the best possible outcomes for our patients. This careful approach minimises the risk of nerve-related complications and contributes to a smoother recovery.

5. Is the cremaster muscle kept intact during the Shouldice repair?

Unlike the original Shouldice technique, where the cremaster muscle is cut, our approach focuses on preserving it. The cremaster muscle has important functions, such as regulating testicle temperature. We believe maintaining the integrity of the cremaster muscle offers more benefits than the potential advantages of cutting it.

6. How long is the recovery period after a Shouldice repair?

Recovery times can vary, but most patients can resume light activities within a few hours after surgery. Full recovery, including returning to strenuous activities or heavy lifting, usually takes about 4 to 6 weeks. Individual recovery may vary, and it’s important to follow the specific guidance provided by your surgeon.

7. What are the success rates and potential risks associated with the Shouldice repair?

The Shouldice repair is known for its high success rate, when performed by an experienced surgeon. Specifically, the recurrence rate for our Shouldice repairs is around 1 to 2% for small hernias and 2 to 5% for larger hernias. These figures demonstrate the procedure’s effectiveness, especially when performed by experienced surgeons. However, as with any surgical procedure, there are potential risks, such as infection, bleeding, and post-operative pain. The risk of chronic pain or discomfort is generally lower compared to mesh repairs. It’s important for you to discuss individual risks and concerns with our team to gain a comprehensive understanding of the procedure.

8. Can I return to my regular activities and exercise routine post-Shouldice repair?

Yes, you can return to your regular activities and exercise routines after a full recovery from the Shouldice repair. However it’s important to gradually reintroduce activities, following the guidance of our surgeon and also by listening to your body. Light exercises can be resumed within a week, but strenuous activities should be approached with caution until full recovery is confirmed. After full recovery, there are no limitations in terms of the load and intensity of activities and exercise. Patients can confidently return to their previous levels of activity and even seek to improve further, without restrictions.

9. Does the Shouldice repair also work for recurrent hernias?

Absolutely, the Shouldice repair is indeed an option for those experiencing a recurrent hernia after previous repairs. Whether your initial repair involved laparoscopic mesh placement, the Shouldice technique, or other tissue-based methods, we can typically perform the Shouldice repair with ease. If your original hernia was repaired using an open mesh technique, such as the Lichtenstein method, we might need to remove some of the mesh before we can successfully apply the Shouldice technique to your recurrent hernia.

10. Does the Shouldice repair cause tension in the groin?

The idea of a “tension-free” repair is more of a marketing term used by various hernia repair methods to highlight their approach. However, a certain degree of tension is inherent in the nature of hernia repairs. This includes the Shouldice repair, as well as other natural-tissue and mesh-based techniques.

When we talk about repairing a hernia, what we’re essentially doing is bringing tissues together to mend a tear or weakness in the abdominal wall. This process naturally introduces some initial tension to the area as the muscles and tissues are aligned for healing. However, this sensation is typically mild and temporary. The human body is remarkably adaptable. Just like muscles gradually stretch and strengthen in response to exercise, the tissues in the abdominal area adjust and heal post-repair, leading to a reduction in initial tension through a process known as muscular adaptation.

This healing journey mirrors natural body changes, similar to those experienced by weight lifters as their muscles adapt to lifting heavy weights, or the incredible adjustments a woman’s body makes during pregnancy. So, while there may be some initial, minor tension felt with the Shouldice repair, it’s a part of the natural healing process, easing off as your body adapts and recovers.

11. What is the difference between a direct and indirect hernia?

A direct hernia occurs due to a weakness in the abdominal wall, commonly seen in older individuals. An indirect hernia, however, protrudes through the inguinal canal following the spermatic cord, and is often a condition present from birth. In terms of prevalence, indirect hernias are more common than direct hernias. However, since the Shouldice repair is designed to address both direct and indirect hernias at the same time, it’s not necessary for you to distinguish between them.

Terminology

Learn more about the hernia terms used on this page, in our simple, easy-to-understand glossary.

External oblique aponeurosis

The external oblique aponeurosis functions as a connecting tissue that links the external oblique muscle to the bones in the abdominal region (the lower ribs and the pelvis). Think of it as a robust sheet that fastens the muscle to its surroundings. This connection offers stability and support to the muscle, enhancing the overall strength and functionality of your abdominal area. While its main role is in muscle attachment, it also contributes to the structural integrity of the abdominal wall.

The inguinal canal

The inguinal canal is a canal located in the lower abdomen, next to the groin. It acts as a pathway for structures like blood vessels and the spermatic cord to pass through. This canal plays an important role in male anatomy and sexual functionality.

The internal ring

Consider the internal ring to be a sort of gateway in the lower abdomen, near the groin. It’s a natural opening in the abdominal wall. This opening allows blood vessels and the spermatic cord to travel between your inner abdomen and the groin area. The internal ring, similar to how a door allows you to go between rooms, allows various parts of the body to move around where they need to be. It’s a natural component of how our bodies are constructed.

Hernia sac

A hernia sac is a delicate, pouch-like structure that develops when a section of an organ or fatty tissue pushes through a vulnerable area or gap in the surrounding muscle or connecting tissue. Think of it as a small pocket that accommodates the bulging tissue. The size and location of hernia sacs can differ depending on the type of hernia.

The inguinal ligament

Imagine the inguinal ligament as a kind of strong, flexible band that runs from the front of your hip bone to the pubic bone. It’s like a support belt for your lower abdomen and groin area. This ligament helps hold things in place and provides stability to the region. Just like how a belt supports your trousers, the inguinal ligament supports the structures in your lower belly, making sure everything stays where it should be.

Internal oblique muscle

The internal oblique is one of the three layers of muscles that make up your abdominal wall. In the inguinal area, the internal oblique muscle is sandwiched between the external oblique muscle and the transverse abdominis muscle. Think of the internal oblique muscle as a layer of muscle in your abdomen, just beneath your skin and the surface muscles. It’s like a hidden layer that adds strength and support to your belly. This muscle helps you twist, bend, and move your torso.

The spermatic cord

Think of the spermatic cord as a kind of bundle or cord that contains important things like blood vessels, spermatic vessels, and nerves. It’s located in your groin area and connects your testicle to to the base of your penis, through your abdominal wall. This cord is like a highway that allows sperm to travel between your testicle and your penis. It’s an essential part of your anatomy, that mainly plays a role in the reproduction system.

Resorbable sutures

Resorbable sutures are designed to have a controlled rate of breakdown in your body. This means that over time, the sutures gradually dissolve and get absorbed by your body. They’re made from a substance that breaks down through a natural process called hydrolysis.

Further reading

Explore our curated selection of scientific literature for a deeper understanding of the Shouldice technique.

- Bendavid, R., Koch, A., Iakovlev, V.V. (2017). The Shouldice Repair 2016. In: Hope, W., Cobb, W., Adrales, G. (eds) Textbook of Hernia. Springer, Cham. ↗

- Lorenz R, Arlt G, Conze J, Fortelny R, Gorjanc J, Koch A, Morrison J, Oprea V, Campanelli G. Shouldice standard 2020: review of the current literature and results of an international consensus meeting. Hernia. 2021 Oct;25(5):1199-1207. ↗

- Schumpelick V. Does every hernia demand a mesh repair? A critical review. Hernia. 2001 Mar;5(1):5-8. ↗

- Bendavid R. New techniques in hernia repair. World J Surg. 1989 Sep-Oct;13(5):522-31. ↗

- Koch A, Lorenz R, Meyer F, Weyhe D. Hernia repair at the groin—who undergoes which surgical intervention? Zentralbl Chir. 2013;138:410–7. ↗

- Bendavid R, Howarth D. Transversalis fascia rediscovered. Surg Clin North Am. 2000 Feb;80(1):25-33. ↗

- Shouldice EB. The Shouldice repair for groin hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2003 Oct;83(5):1163-87, vii. ↗

- Bendavid R. Biography: Edward Earle Shouldice (1890-1965). Hernia. 2003 Dec;7(4):172-7. ↗

- Bendavid R, Mainprize M, Iakovlev V. Pure tissue repairs: a timely and critical revival. Hernia. 2019 Jun;23(3):493-502. ↗