Free video consultation | Tuesday 24th February

The next session will be on

Tuesday 24th February 2026

With Dr. Martin Wiese

Book a free video consultation with one of our surgeons, to discuss your symptoms, explore treatment options, and receive expert advice, all from the comfort of your home.

Open mesh removal explained

Our hernia mesh removal technique directly addresses complications caused by plastic mesh implants, following open mesh (Lichtenstein) hernia surgery. Our surgeons carefully removes the problematic mesh and repair the affected area using the natural tissue Shouldice technique. This approach prioritises pain relief and reduces the risk of further complications, helping you return to your normal, active life without restrictions.

Chronic pain after open mesh hernia surgery

Chronic groin pain affects between 12% and 37% [1-7] of all patients following hernia surgery with mesh, significantly impacting their quality of life. For open (Lichtenstein) mesh repairs, pain is often caused by complications such as nerve entrapment, mesh contraction, shrinkage, migration, or chronic inflammation. These issues can lead to persistent discomfort, limited mobility, a foreign body sensation and chronic pain or inflammation. For patients with these symptoms, removing the mesh may provide relief and help restore normal function.

Open vs. Laparoscopic mesh removal

Lichtenstein (open) mesh is placed just beneath the skin, making removal more straightforward compared to laparoscopically placed mesh, which is located deeper behind the abdominal muscles. This page focuses only on the step-by-step process for removing mesh placed with an open technique. If you have a laparoscopically placed mesh and are experiencing complications, you can contact us to discuss whether removal is possible in your case.

Starting your operation

Following the administration of a general anaesthetic, we start your mesh removal by making a small 5cm incision in the lower abdominal area. For open mesh removals, our surgeons typically make the incision through the same scar used when the mesh was originally placed. This approach minimises additional scarring and allows for direct access to the mesh, ensuring a more precise and effective removal. Throughout the procedure, a dedicated anaesthetist is on hand to ensure your comfort and well-being.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

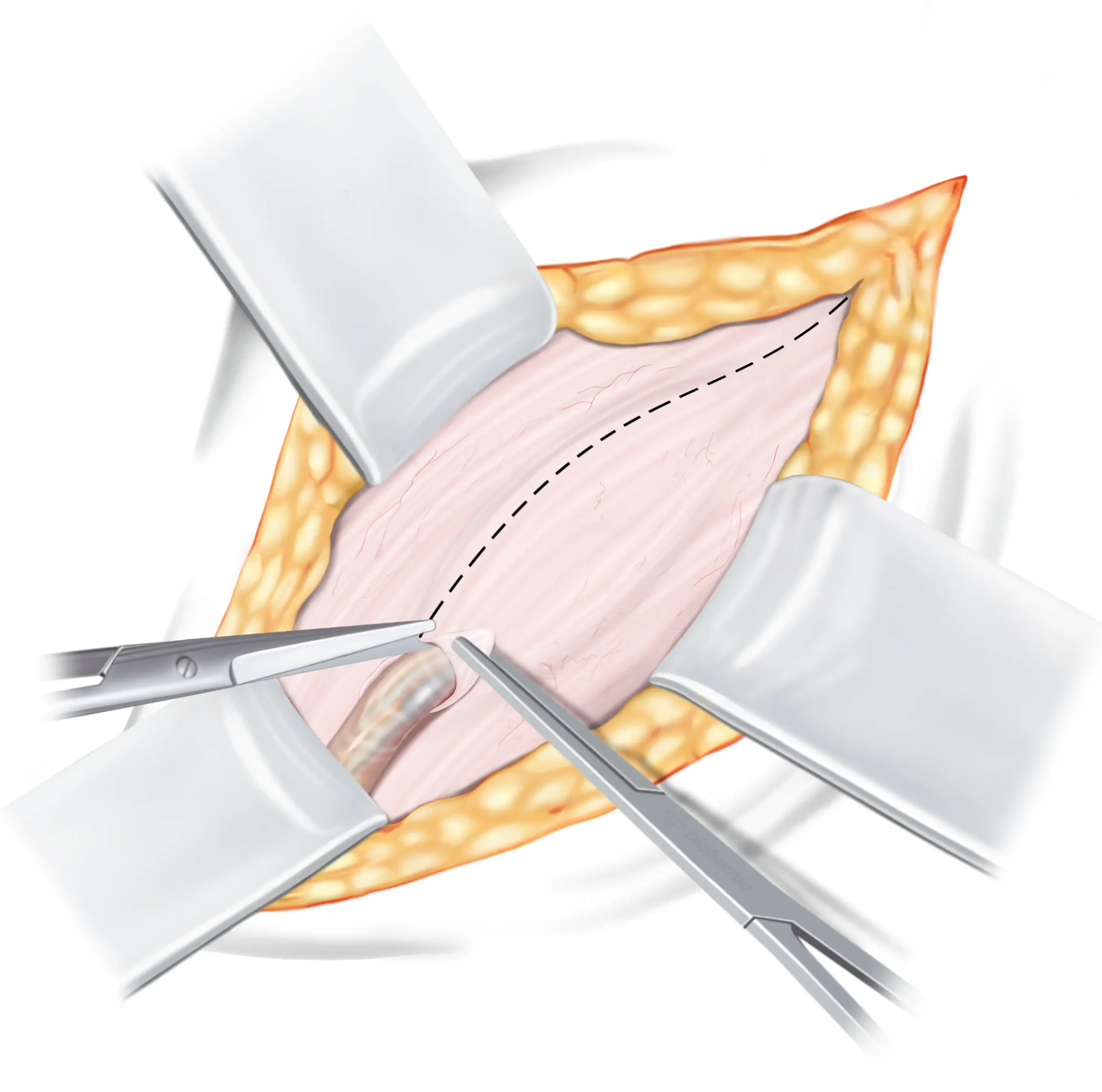

Opening the inguinal canal

The first tissue we encounter is the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle ↓, which forms the roof of the inguinal canal ↓ . To gain access to the inguinal canal for the repair, we need to open this tissue. It is important to note that opening the external oblique aponeurosis (EOA) does not have any negative impact on its functionality, as it will be closed again during the final step of the operation. Once opened, the spermatic cord ↓ is safely pulled to the side and the two flaps of the external oblique aponeurosis are carefully retracted as they will be utilised later in the repair process.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The external oblique aponeurosis is incised from the superficial inguinal ring past the deep inguinal ring. After opening, the upper leaf of external oblique is slightly elevated and undermined with a finger, to free it from the underlying internal oblique muscle, or adhesions to the mesh.

Inguinal ligament

Subcutaneous fat

Upper flap of external

oblique aponeurosis (EOA)

Spermatic cord

Synthetic mesh

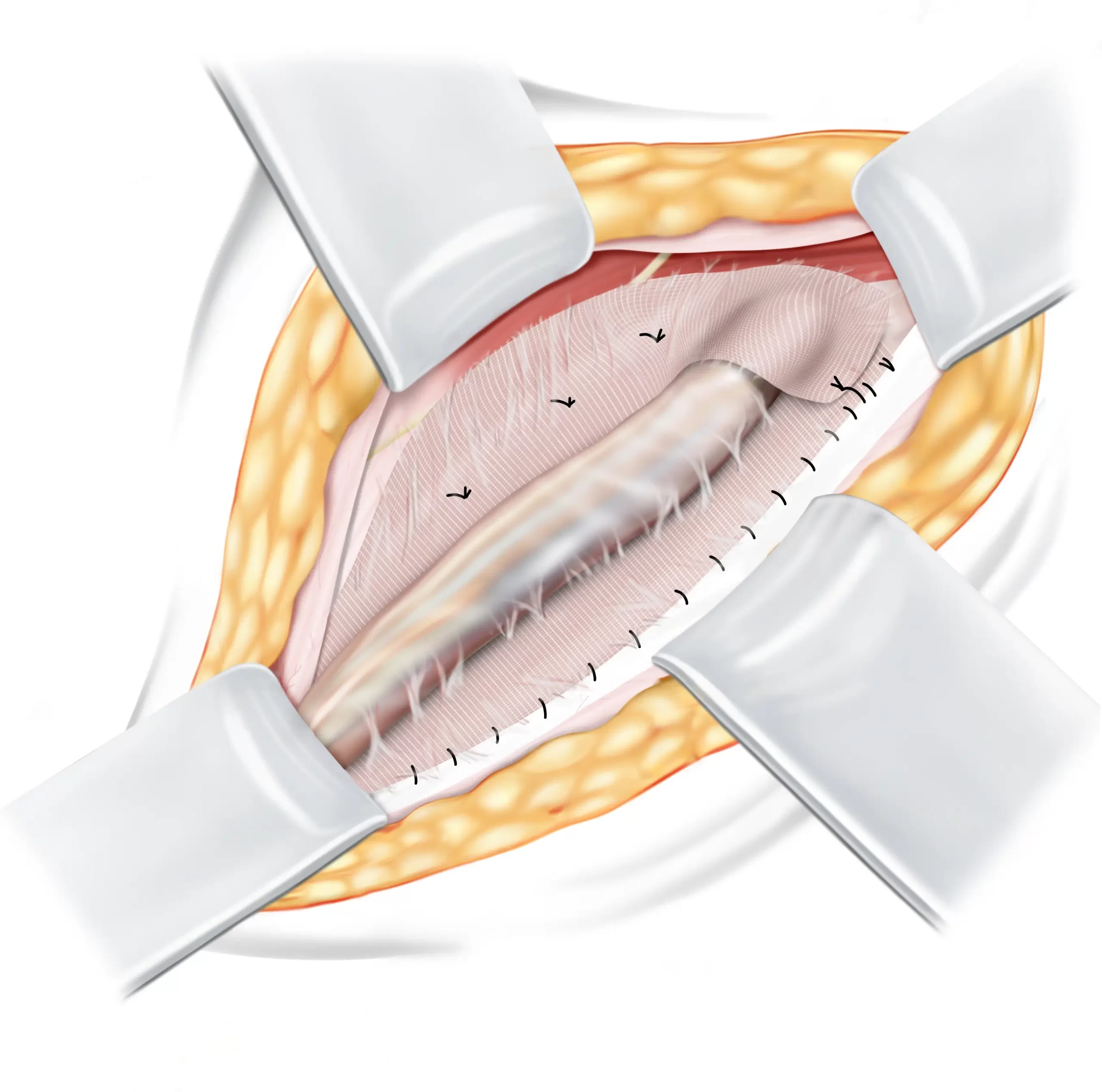

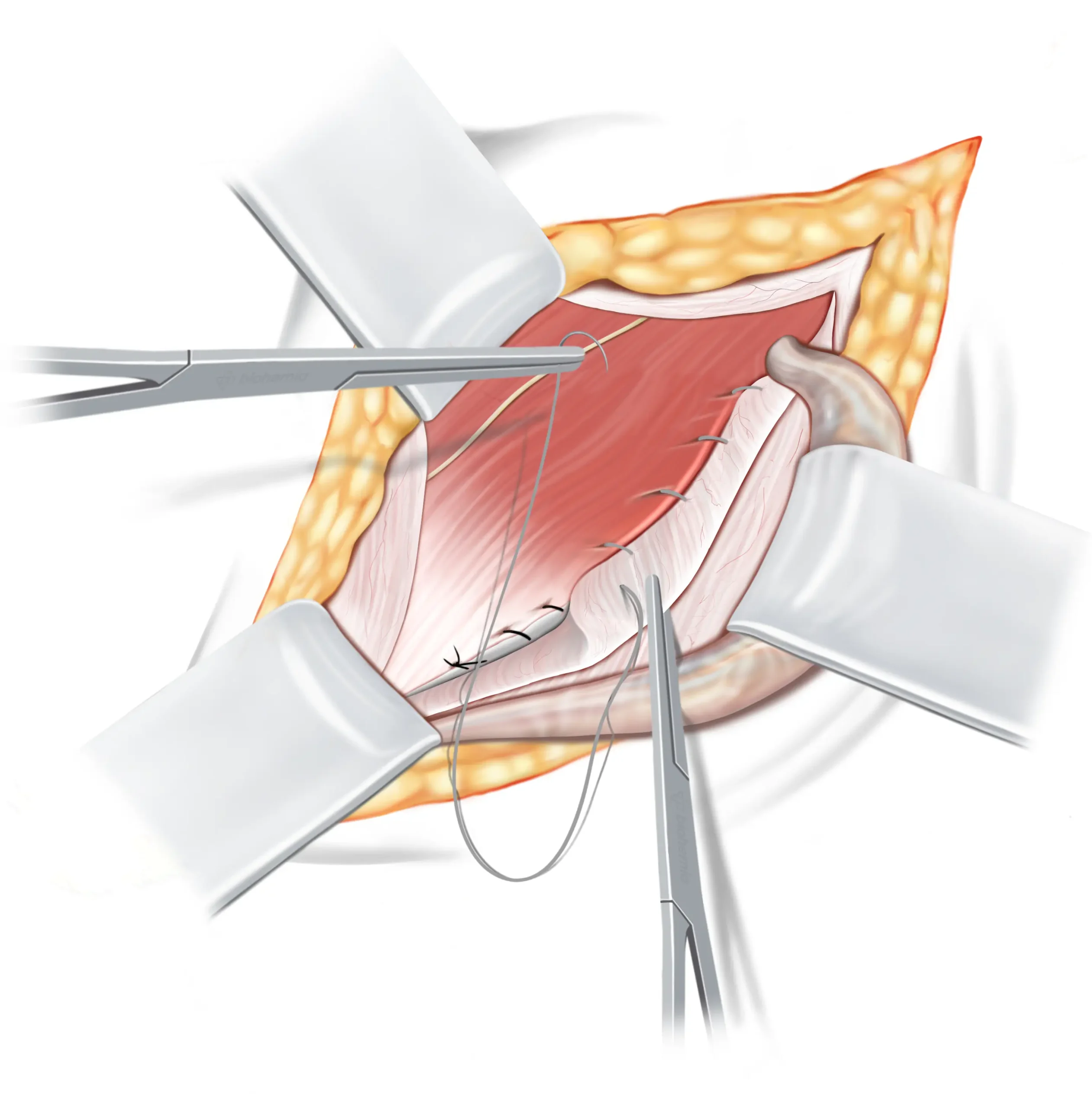

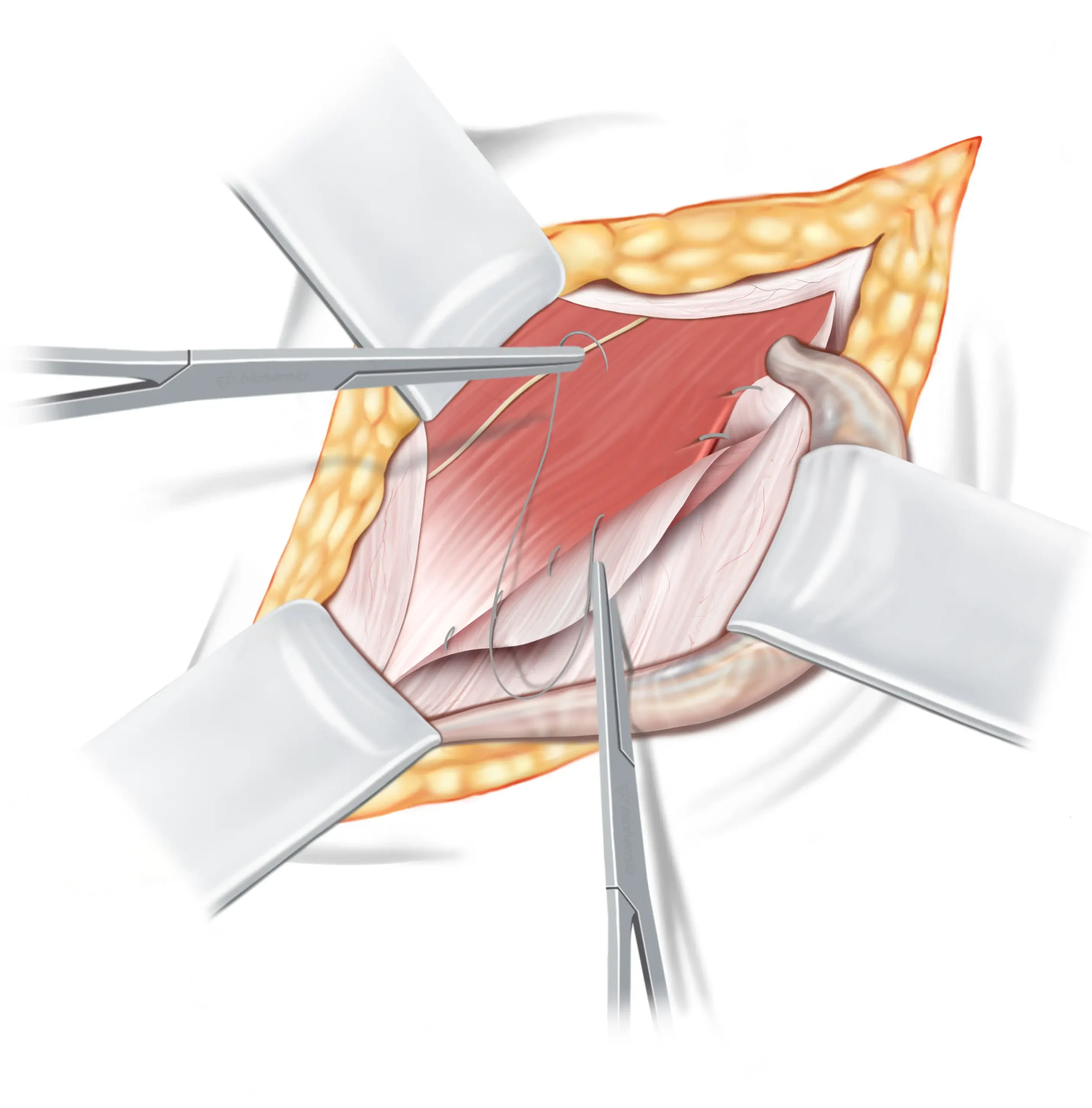

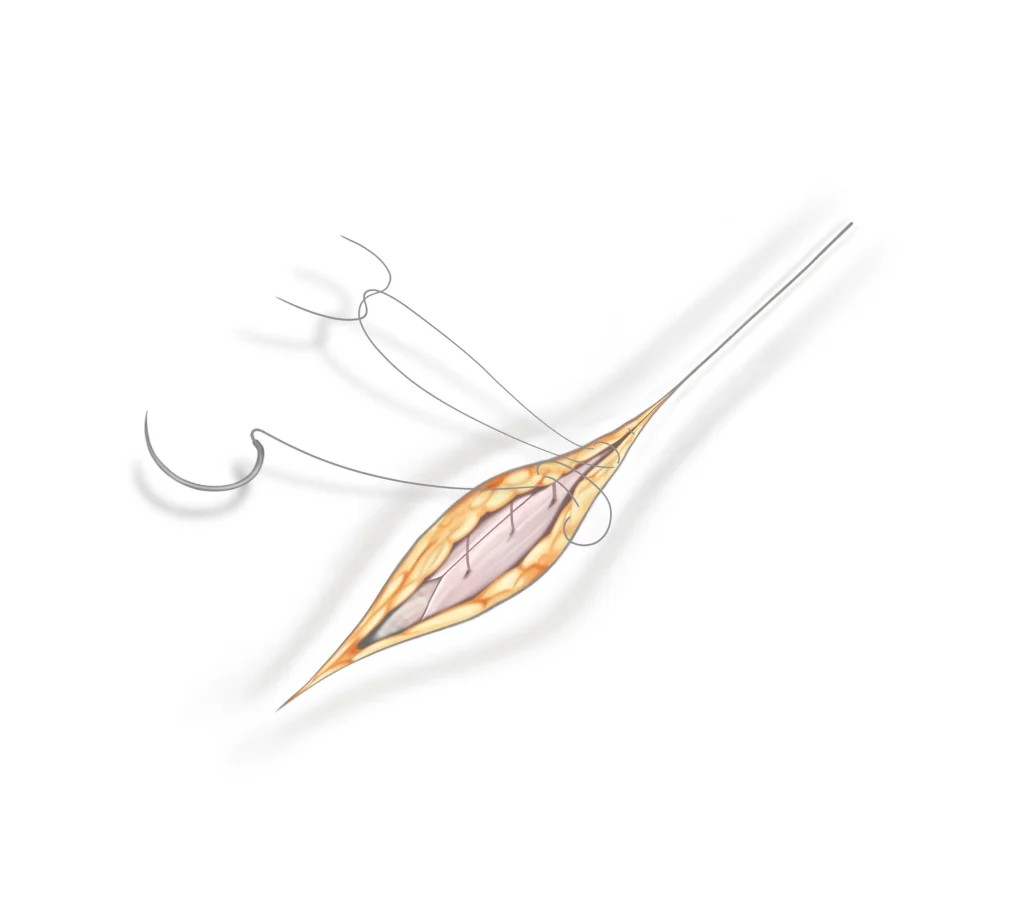

Removing the mesh

Our surgeon starts by carefully removing the tackers or sutures that attach the mesh to surrounding tissues. This delicate process involves freeing the mesh from any adhesions that may have formed with the surrounding tissue, like the spermatic cord or muscles. If necessary, the surgeon will also remove any adhesions to nearby nerves, ensuring these are handled with care. In cases where a nerve has regrown through the mesh, it may need to be carefully cut to prevent ongoing pain. Once the tackers and adhesions are addressed, the surgeon will remove the mesh completely, or partially, if complete removal is not possible due to extensive integration with the tissue.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

At this stage of the mesh explantation, the surgeon meticulously removes the tackers or sutures, which secure the mesh to the inguinal ligament, the internal oblique muscle and other surrounding tissues. This step involves careful dissection to release the mesh from any fibrotic adhesions to the surrounding tissues, ensuring minimal trauma to the area. The surgeon will also pay close attention to neurovascular structures, removing any adhesions involving the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, or genitofemoral nerves to prevent neuropathic complications. In cases where a nerve, has become entrapped or has regrown through the mesh, a neurectomy may be performed to relieve chronic pain. Depending on the extent of mesh integration with surrounding tissues, partial or complete removal of the mesh is achieved.

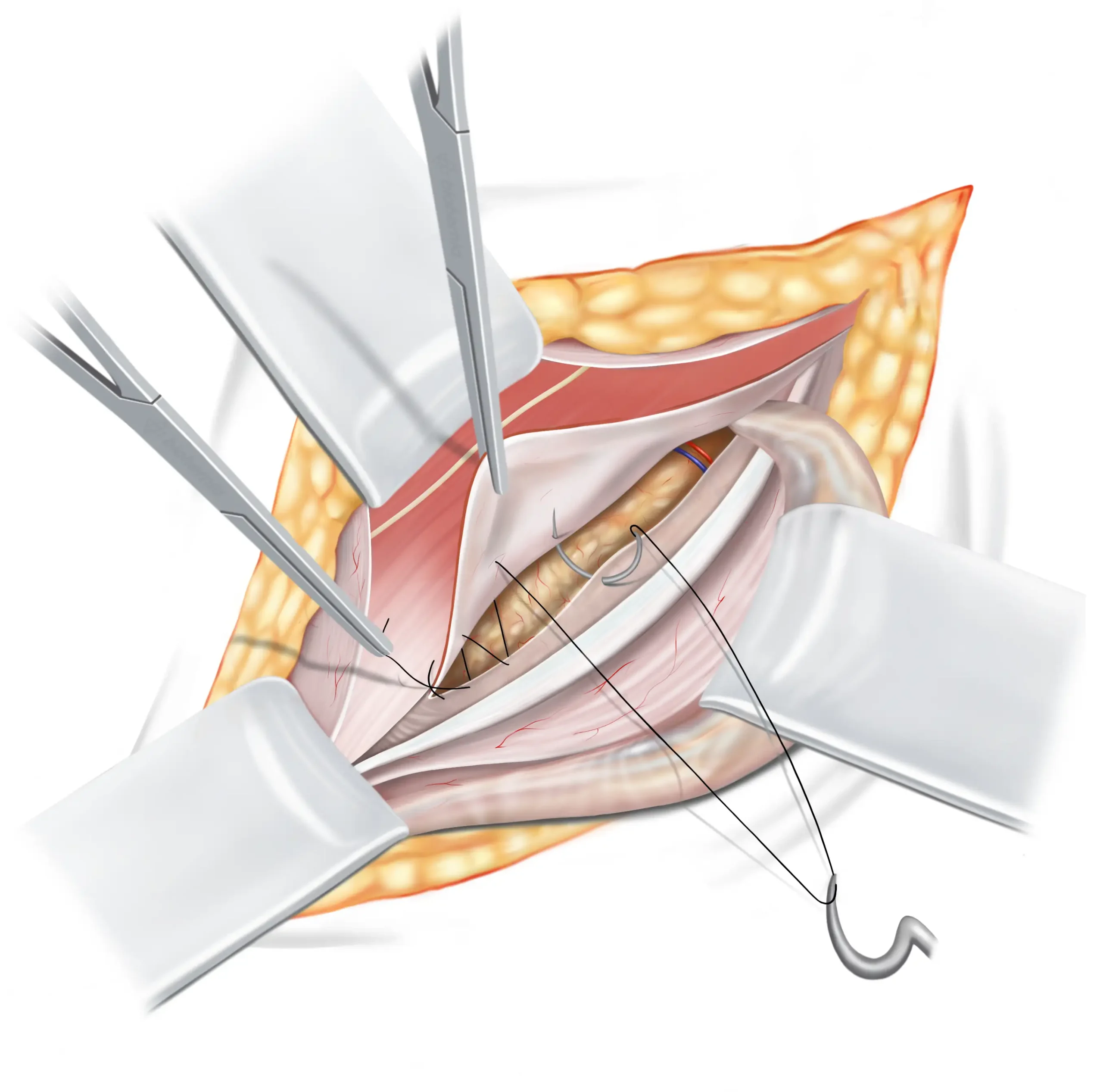

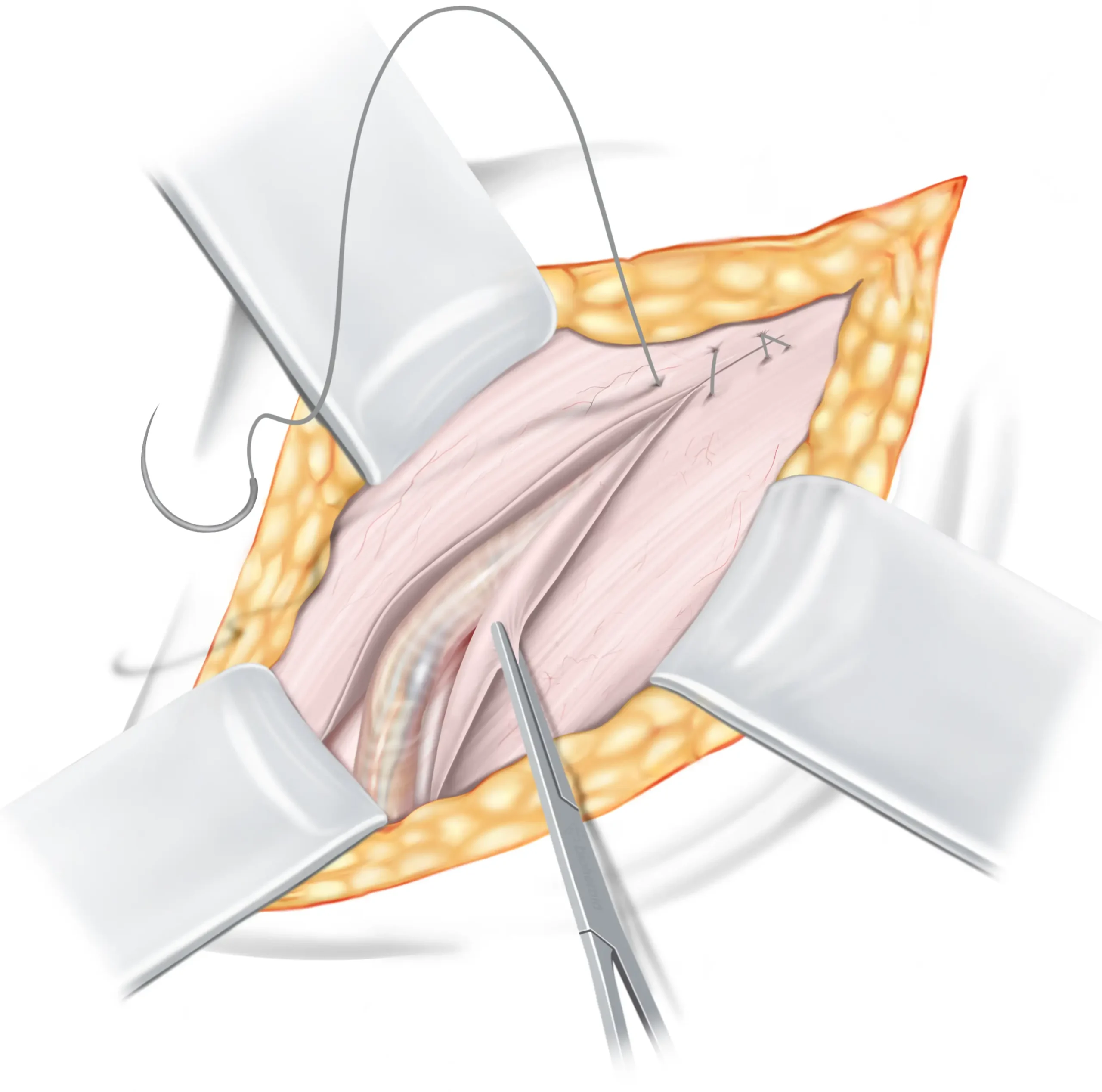

Shouldice repair sutures

Now that the mesh has been removed, our surgeon can proceed with the Shouldice repair to address the weakness in the groin. The Shouldice repair involves a four-layered suturing technique that overlaps layers of tissue in the groin, reinforcing the weakened area. This natural tissue repair creates a strong, durable barrier, effectively preventing the recurrence of both direct and indirect hernias, without the need for a plastic mesh.

First suture line

The first suture is secured, leaving a bit of it extended. This extended part will later connect with the second suture line. As this suture travels sideways, it joins three layers of tissues and muscles to the lower flap of the transversalis fascia. The suture then proceeds to the internal ring.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The suture is tied off, leaving a long tail to merge with the returning suture from the second line. As the initial suture line moves laterally, it encompasses the triple layer from the medial side over to the iliopubic tract on the lateral side. A section, roughly 1 cm in width, of the medial flap is crafted to dangle freely. About halfway towards the internal ring, the edge of the rectus becomes unavailable and is left out from the continuous suture, which then carries on to the internal ring.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Inguinal ligament

Iliohypogastric nerve

Internal oblique muscle

Extraperitoneal fat

Second suture line

At the internal ring the suture line reverses, attaching a hanging part of the three layers of tissue to the inguinal ligament. When it reaches the beginning of the first suture line, it is secured to the tail of the first suture, that we left earlier.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

Upon reaching the internal ring, the suture reverses to form the second line. This line moves towards the pubic crest, integrating the loose edge of the triple layer to the inguinal ligament. Close to the pubic crest, the suture connects and secures with the earlier left tail end.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Iliohypogastric nerve

Inguinal ligament

Internal oblique muscle

Flap of three layers:

1. Internal oblique

2. Transversus abdominis

3. Transversalis fascia

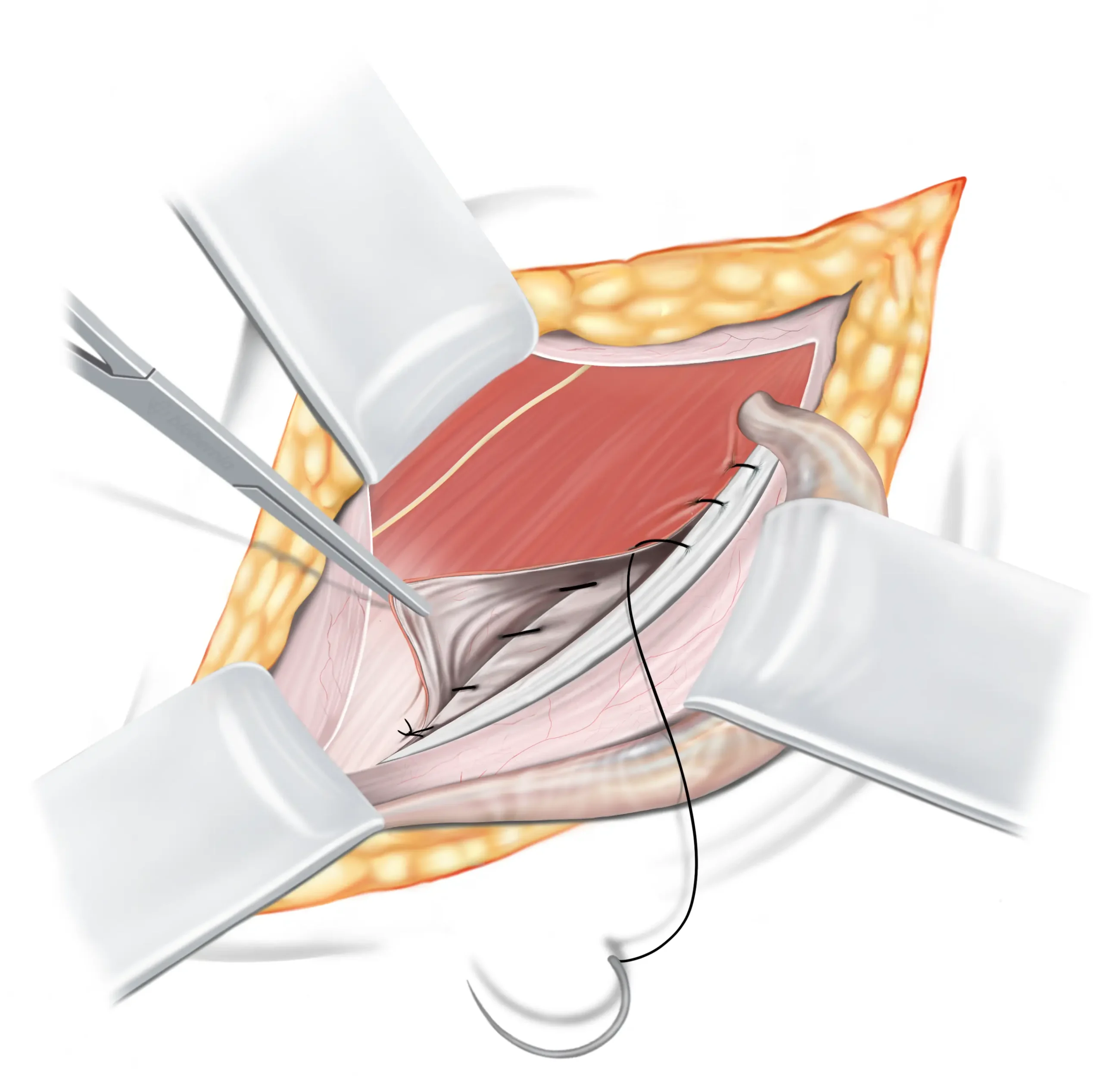

Third suture line

We’ll proceed to use a second suture now, which will be used for both the third and fourth row. For this step we use a resorbable suture ↓. It starts near the internal ring, picking up the middle part of our three-layered flap, then it shifts to include a bit of the EOA. It runs close to our previous suture row but closer to the surface, effectively forming a secondary inguinal ligament.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

We’ll now proceed with the second suture, which will be used for both the third and fourth lines, for which we use a resorbable suture. Starting from the internal ring, the third line first engages with the medial side of the triple layer, then shifts to integrate the inner layer of the EOA, running adjacent to the second line but at a more surface level, thus creating a sort of second inguinal ligament.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Retracted flap external

oblique aponeurosis

Internal oblique muscle

Iliohypogastric nerve

Upper flap of external

oblique aponeurosis

Fourth suture line

The suture line then reverses back towards the inguinal ring, and ends by securely tying both ends of the suture line together.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

Upon reaching the pubic crest, the fourth line proceeds back towards the internal ring, seamlessly merging the triple layer with the interior side of the EOA, as though creating another inguinal ligament. Concluding at the internal ring, both ends of the sutures are securely tied together.

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

Iliohypogastric nerve

Internal oblique muscle

Retracted flap external

oblique aponeurosis

Upper flap external

oblique aponeurosis

Spermatic cord

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

Finalising your repair

The spermatic cord is carefully returned to its natural position, and the inguinal canal is closed by bringing together the fascia of the external oblique muscle and securely suturing it with resorbable sutures.

Closing the skin

After the procedure, the incision is closed using sutures that the body naturally absorbs. Therefore, there is no need for you to return for suture removal, as these sutures dissolve on their own. Local anaesthetics will also be applied, which could make the area look somewhat swollen after the operation, but this is a typical response and helps reduce pain after the operation.

Wound care

In the final steps, medical glue and Steri-Strips are applied to your wound. These strips aid in holding the wound’s edges together, minimising potential scarring during the healing process. You can safely remove the strips after one week.

DISCLAIMER

The illustrations displayed on this page have been adjusted in size—some enlarged and others reduced—to enhance understanding. They are intended to provide a simplified explanation of the operation technique and do not accurately portray the complex nature of human anatomy, nor do they convey the intricate challenges encountered during actual surgical procedures. Within the human body, everything is interlinked, making the identification of tissues, nerves, and blood vessels more challenging than what is suggested by the illustrations. Consequently, considerable experience and surgical skill are essential to accurately and effectively perform the operation technique illustrated.

Frequently asked questions

1. Why would I need a mesh removal?

Mesh removal may be necessary if you’re experiencing chronic pain, discomfort, or other complications following a hernia repair with mesh. Common issues include nerve entrapment, infection, inflammation, or a foreign body sensation caused by the mesh.

2. How long will recovery take after mesh removal surgery?

Recovery after mesh removal surgery typically takes a few weeks, but full recovery can take up to 12 weeks. You’ll need to stay in the area for several days after the procedure for follow-up appointments. During this time, your surgeon will monitor your healing and provide personalised guidance to ensure a smooth recovery.

3. What are the risks of hernia mesh removal?

As with any surgery, mesh removal carries risks, such as infection, bleeding, or damage to surrounding tissues and nerves. However, our surgeons take special care to avoid nerve damage and handle any nerve entrapments that may have occurred due to the mesh.

4. Will I need additional repair after the mesh is removed?

Yes, during the same operation when the mesh is removed, the weakness in your groin will be repaired. Our surgeons often use the Shouldice repair, a non-mesh technique that reinforces the weakened area using your own tissues, creating a natural and durable solution. There is no need for a separate surgery for this repair.

5. What are the success rates for mesh removal surgery?

In 95% of cases, mesh removal is possible. Based on Dr. Koch’s extensive experience, including research on over 200 patients who had inguinal hernia mesh removal, the following success rates were observed:

- 25% of patients became completely pain-free after surgery

- 60% of patients experienced a significant reduction in pain – meaning they could return to a better quality of life with far less discomfort.

- Together, this means that 85% of patients saw meaningful improvements in their symptoms, highlighting the effectiveness of mesh removal surgery.

A small percentage of patients experienced less favorable outcomes:

- 10% reported little to no change in their symptoms, while

- 5% experienced more pain (4% with slightly more pain and only 1% with significantly more pain).

These results demonstrate the high success rate of mesh removal surgery in relieving pain and improving the quality of life for the vast majority of patients. With minimal risks and a significant chance of improvement, mesh removal surgery offers hope for those dealing with the often debilitating effects of mesh complications.

6. Does the Shouldice repair cause tension in the groin?

The idea of a “tension-free” repair is more of a marketing term used by various hernia repair methods to highlight their approach. However, a certain degree of tension is inherent in the nature of hernia repairs. This includes the Shouldice repair, as well as other natural-tissue and mesh-based techniques.

When we talk about repairing a hernia, what we’re essentially doing is bringing tissues together to mend a tear or weakness in the abdominal wall. This process naturally introduces some initial tension to the area as the muscles and tissues are aligned for healing. However, this sensation is typically mild and temporary. The human body is remarkably adaptable. Just like muscles gradually stretch and strengthen in response to exercise, the tissues in the abdominal area adjust and heal post-repair, leading to a reduction in initial tension through a process known as muscular adaptation.

This healing journey mirrors natural body changes, similar to those experienced by weight lifters as their muscles adapt to lifting heavy weights, or the incredible adjustments a woman’s body makes during pregnancy. So, while there may be some initial, minor tension felt with the Shouldice repair, it’s a part of the natural healing process, easing off as your body adapts and recovers.

Terminology

Learn more about the hernia terms used on this page, in our simple, easy-to-understand glossary.

External oblique aponeurosis

The external oblique aponeurosis functions as a connecting tissue that links the external oblique muscle to the bones in the abdominal region (the lower ribs and the pelvis). Think of it as a robust sheet that fastens the muscle to its surroundings. This connection offers stability and support to the muscle, enhancing the overall strength and functionality of your abdominal area. While its main role is in muscle attachment, it also contributes to the structural integrity of the abdominal wall.

The inguinal canal

The inguinal canal is a canal located in the lower abdomen, next to the groin. It acts as a pathway for structures like blood vessels and the spermatic cord to pass through. This canal plays an important role in male anatomy and sexual functionality.

The internal ring

Consider the internal ring to be a sort of gateway in the lower abdomen, near the groin. It’s a natural opening in the abdominal wall. This opening allows blood vessels and the spermatic cord to travel between your inner abdomen and the groin area. The internal ring, similar to how a door allows you to go between rooms, allows various parts of the body to move around where they need to be. It’s a natural component of how our bodies are constructed.

Lichtenstein repair

The Lichtenstein repair is an open surgical technique commonly used to treat inguinal hernias. During this procedure, the surgeon makes an incision in the groin area to access the hernia directly. A plastic mesh is then placed over the weakened area to reinforce the abdominal wall, and the mesh is secured using sutures or tackers.

Unlike laparoscopic repair, which involves making small incisions and using a camera and instruments to repair the hernia from inside the abdomen, the Lichtenstein repair is done through a larger, open incision.

The inguinal ligament

Imagine the inguinal ligament as a kind of strong, flexible band that runs from the front of your hip bone to the pubic bone. It’s like a support belt for your lower abdomen and groin area. This ligament helps hold things in place and provides stability to the region. Just like how a belt supports your trousers, the inguinal ligament supports the structures in your lower belly, making sure everything stays where it should be.

Internal oblique muscle

The internal oblique is one of the three layers of muscles that make up your abdominal wall. In the inguinal area, the internal oblique muscle is sandwiched between the external oblique muscle and the transverse abdominis muscle. Think of the internal oblique muscle as a layer of muscle in your abdomen, just beneath your skin and the surface muscles. It’s like a hidden layer that adds strength and support to your belly. This muscle helps you twist, bend, and move your torso.

The spermatic cord

Think of the spermatic cord as a kind of bundle or cord that contains important things like blood vessels, spermatic vessels, and nerves. It’s located in your groin area and connects your testicle to to the base of your penis, through your abdominal wall. This cord is like a highway that allows sperm to travel between your testicle and your penis. It’s an essential part of your anatomy, that mainly plays a role in the reproduction system.

Resorbable sutures

Resorbable sutures are designed to have a controlled rate of breakdown in your body. This means that over time, the sutures gradually dissolve and get absorbed by your body. They’re made from a substance that breaks down through a natural process called hydrolysis.

Further reading

Explore our sources and curated selection of scientific literature for a deeper understanding of hernia mesh removal surgery & the Shouldice repair technique.

- Aasvang E, Kehlet H (2004) Chronic postoperative pain: the case of inguinal herniorrhaphy. Br J Anaesth 95(1):69–76 ↗

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ (2006) Persistent postsurgical pain:risk factors and prevention. Lancet 367(9522):1618–1625 ↗

- Franneby U, Sandblom G, Nordin P, Nyren O, Gunnarsson U (2006) Risk factors for long-term pain after hernia surgery. Ann Surg 2:212–219 ↗

- Poobalan AS, Bruce J, Smith WC, King PM, Krukowski ZH et al (2002) A review of chronic pain after inguinal herniorrhaphy. Clin J Pain 19(1):48–54 ↗

- Ferzli GS, Edwards E, Al-Khoury G, Hardin R (2008) Post- herniorrhaphy groin pain and how to avoid it. Surg Clin North Am 88(1):203–216 ↗

- Aasvang EK, Bittner R, Kehlet H (2010) Predictive risk factors for persistent postherniotomy pain. Anesthesiology 112(4):957–969 ↗

- Linderoth G, Kehlet H, Aasvang EK et al (2011) Neurophysiological characterization of persistent pain after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Hernia 15:521–529 ↗

- Bendavid, R., Koch, A., Iakovlev, V.V. (2017). The Shouldice Repair 2016. In: Hope, W., Cobb, W., Adrales, G. (eds) Textbook of Hernia. Springer, Cham. ↗

- Lorenz R, Arlt G, Conze J, Fortelny R, Gorjanc J, Koch A, Morrison J, Oprea V, Campanelli G. Shouldice standard 2020: review of the current literature and results of an international consensus meeting. Hernia. 2021 Oct;25(5):1199-1207. ↗

- Schumpelick V. Does every hernia demand a mesh repair? A critical review. Hernia. 2001 Mar;5(1):5-8. ↗

- Bendavid R. New techniques in hernia repair. World J Surg. 1989 Sep-Oct;13(5):522-31. ↗

- Koch A, Lorenz R, Meyer F, Weyhe D. Hernia repair at the groin—who undergoes which surgical intervention? Zentralbl Chir. 2013;138:410–7. ↗

- Bendavid R, Howarth D. Transversalis fascia rediscovered. Surg Clin North Am. 2000 Feb;80(1):25-33. ↗

- Shouldice EB. The Shouldice repair for groin hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 2003 Oct;83(5):1163-87, vii. ↗

- Bendavid R. Biography: Edward Earle Shouldice (1890-1965). Hernia. 2003 Dec;7(4):172-7. ↗

- Bendavid R, Mainprize M, Iakovlev V. Pure tissue repairs: a timely and critical revival. Hernia. 2019 Jun;23(3):493-502. ↗