Free video consultation | Tuesday 24th February

The next session will be on

Tuesday 24th February 2026

With Dr. Martin Wiese

The Desarda repair explained

The Desarda technique was developed in the 1980s by Dr. Mohan Desarda from Pune, India. The technique reinforces the groin’s weakened area with a strip of connective tissue from the same area. We find it especially effective for young, non-smoking patients due to its reliance on strong, healthy tissue.

Considerations for women

Most groin hernia treatments have historically focused on men, leaving a gap in specialised care for women. BioHernia is committed to bridging this gap by offering hernia repairs tailored to women’s unique needs, ensuring effective treatment that respects their specific anatomical and physiological requirements.

1. Assessment of femoral hernias

Femoral hernias are more common in women, with a prevalence of around 15%, they are often overlooked when repairing inguinal hernias. Recognising this, we conduct a thorough assessment to accurately identify and treat a femoral hernia, if present.

2. Protection of the round ligament

The round ligament in women, similar to the spermatic cord in men, is an important structure that runs through the inguinal canal and helps keep the uterus stable. Typically, in a standard inguinal hernia procedure, this ligament is cut. However, we take extra care to protect this ligament, aiming to avoid any harm to it and maintain the structural integrity of the uterus.

3. Tailored approach for women

Recognising that women’s anatomy in the groin area is distinctively different and their tissues are often more resilient than in men, we tailor our approach accordingly. Our surgeons’ extensive experience allows us to adapt our techniques during the operation. This flexibility allows us to switch to less invasive techniques where possible, ensuring a procedure that’s not only effective but also customised to your unique characteristics.

Starting your repair

Following the administration of either a general or local anaesthetic, we start the inguinal hernia repair by making a small 3 to 5cm incision in the lower abdominal area. Throughout the procedure, a dedicated anaesthetist is on hand to ensure your comfort and well-being. The incision is in the lower abdominal area, ensuring that any resulting scar remains discreet, hidden when swimwear or underwear is worn.

Round ligament

of the uterus

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

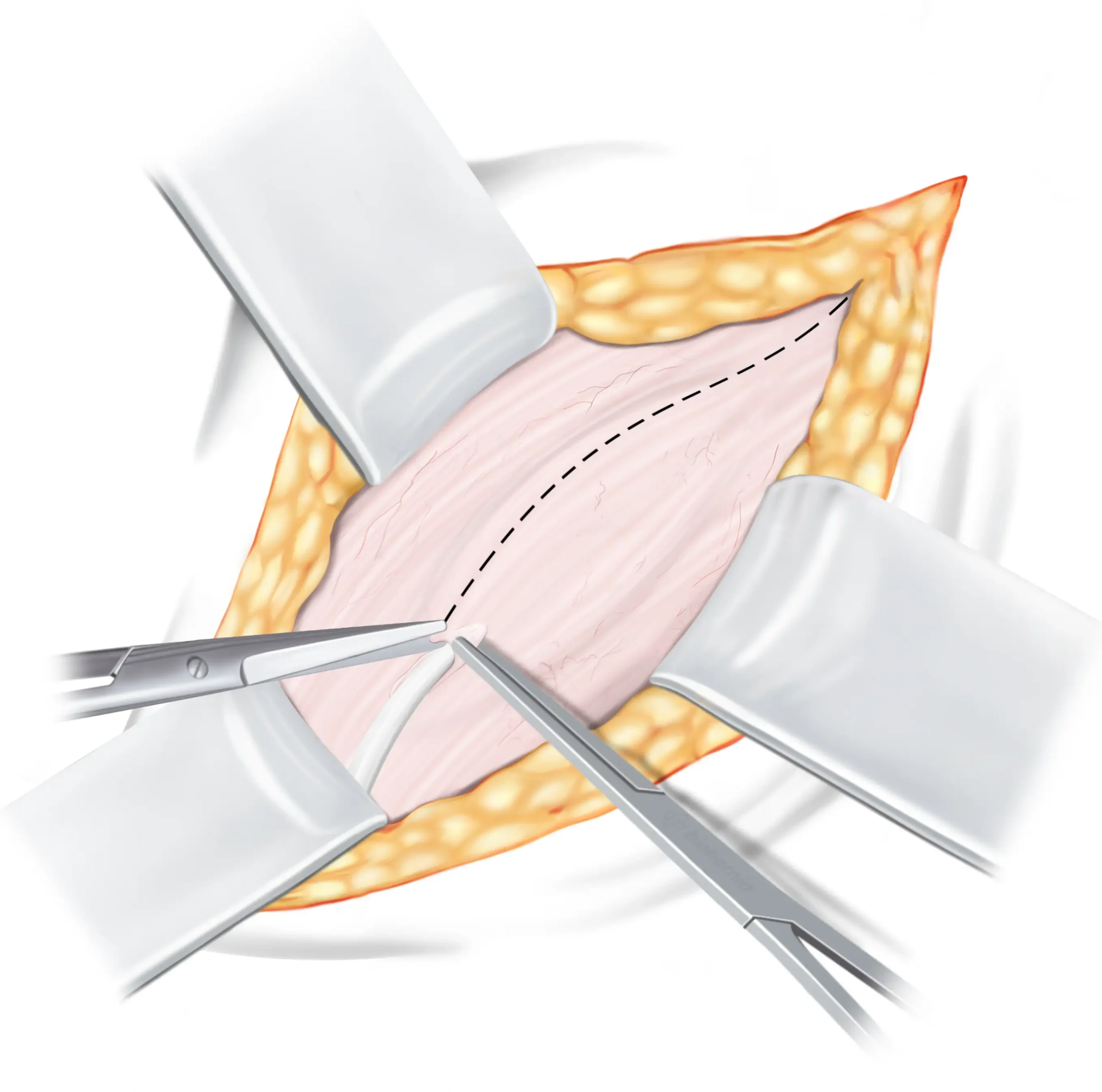

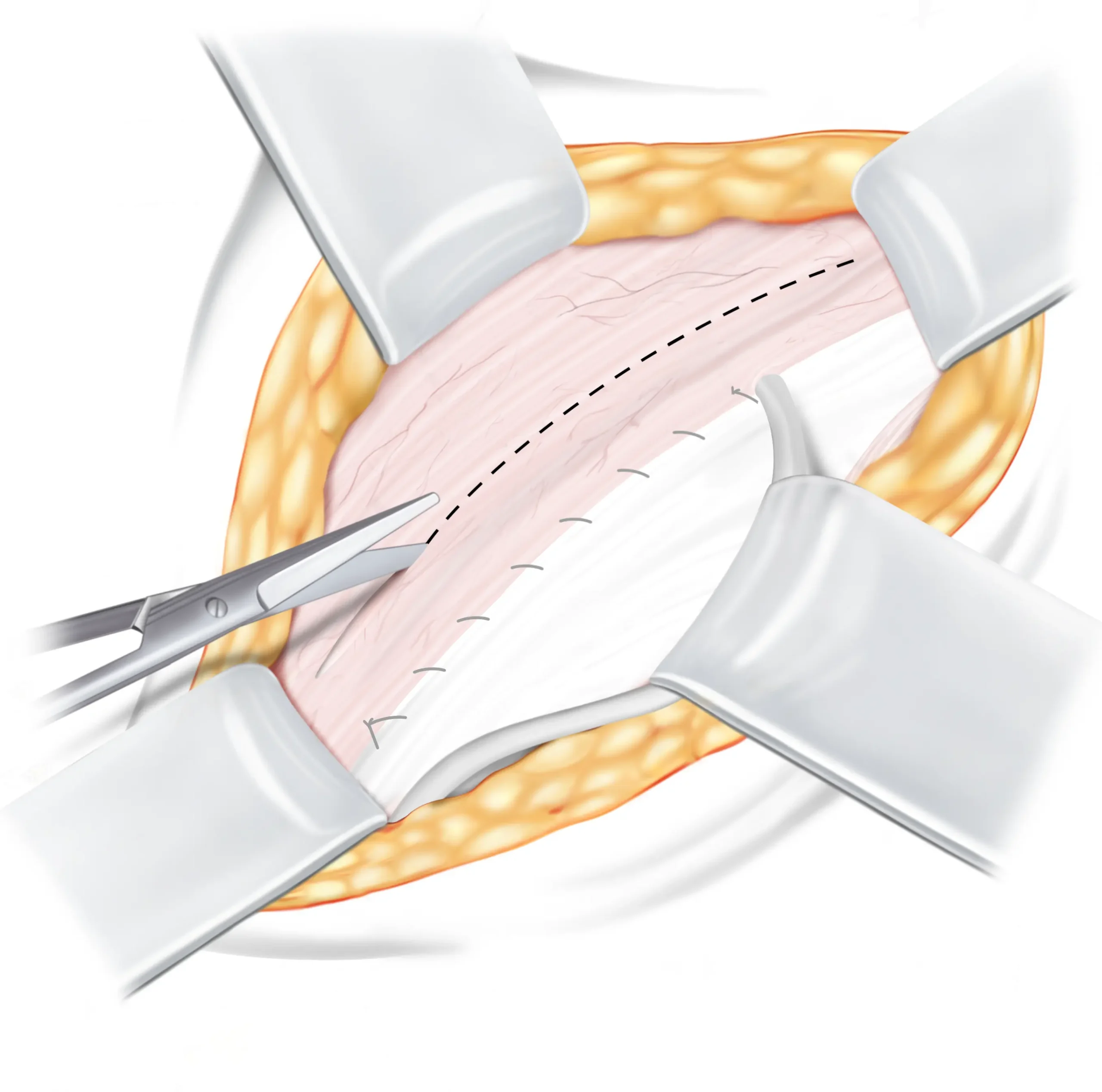

Opening the inguinal canal

The first tissue we encounter is the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle ↓, which forms the roof of the inguinal canal ↓ . To gain access to the inguinal canal for the repair, we need to open this tissue. It is important to note that opening the external oblique aponeurosis (EOA) does not have any negative impact on its functionality, as it will be closed again during the final step of the operation. Once opened, the round ligament of the Uterus↓ is safely pulled to the side and the two flaps of the external oblique aponeurosis are carefully retracted as they will be utilised later in the repair process.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The external oblique aponeurosis is incised from the superficial inguinal ring past the deep inguinal ring. After opening, the upper leaf of external oblique is slightly elevated and undermined with a finger, to free it from the underlying internal oblique muscle.

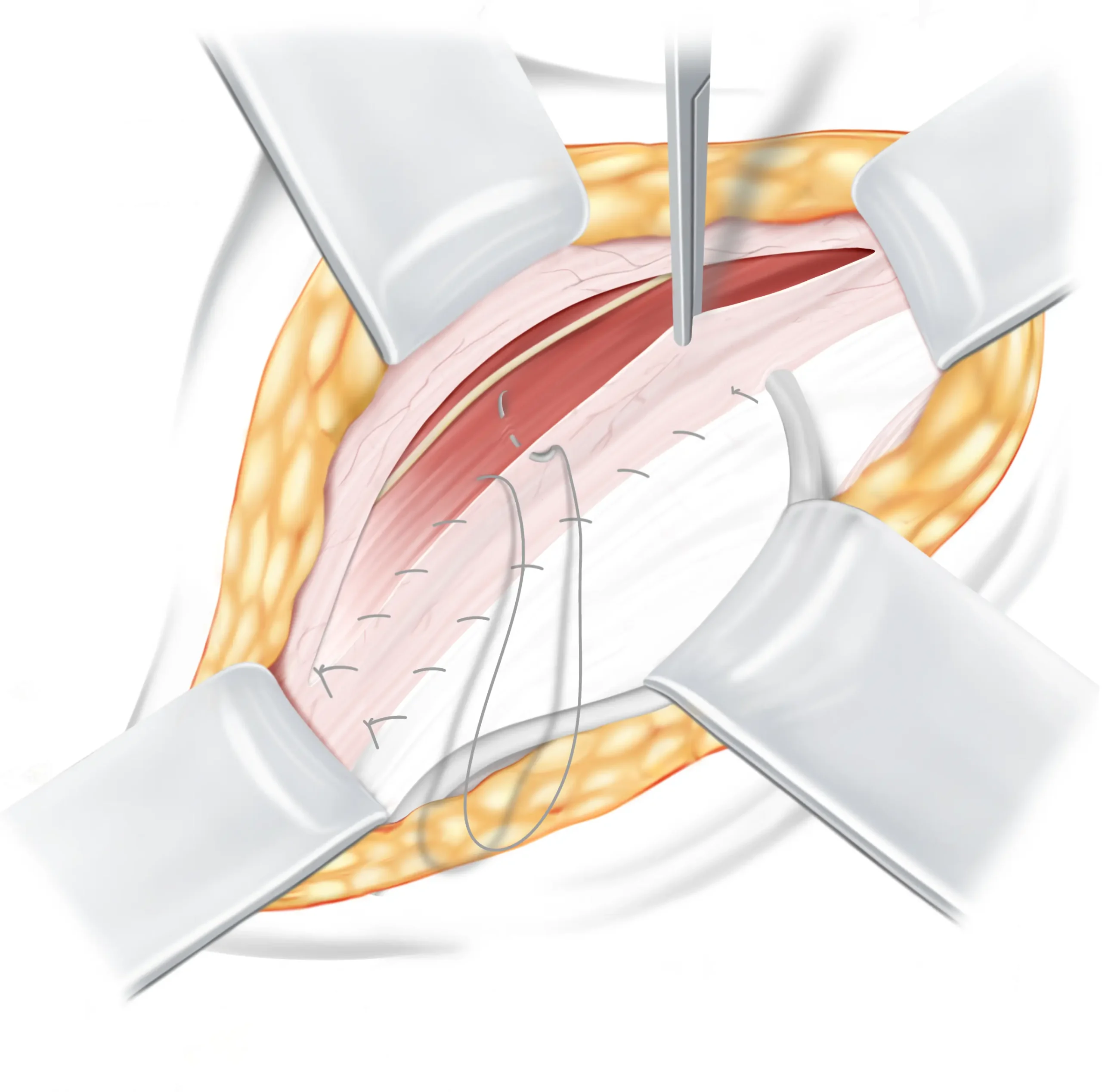

Hernia sac management

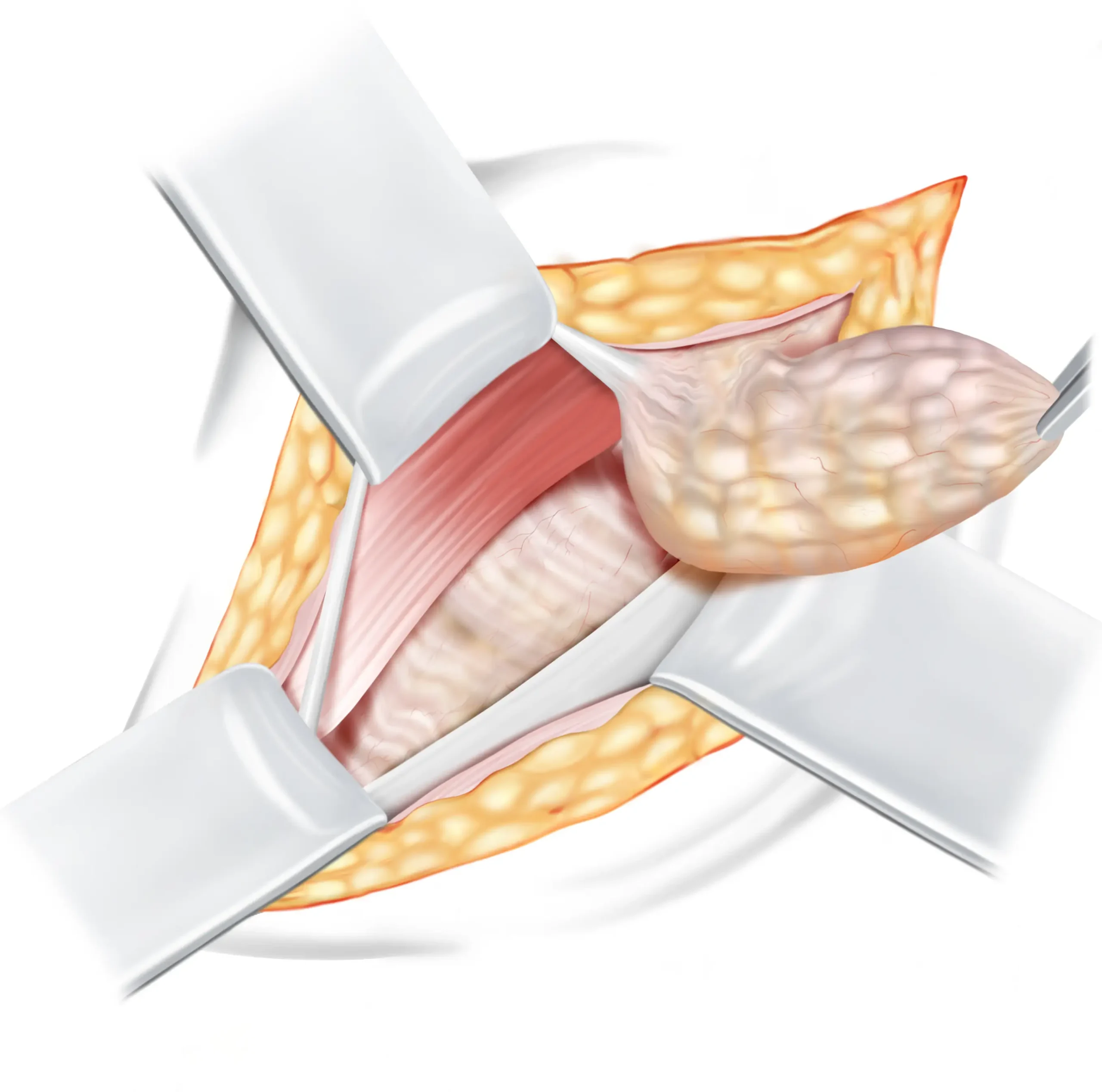

Indirect hernia sac

An indirect hernia is a bulge that emerges from the internal ring, alongside the round ligament. During the repair, this bulge or ‘sac’ ↓ has to be pushed back into its proper place. The sac may be opened to check its contents and then, the sac is tied off close to the internal ring to prevent it from bulging out again. After that, the extra or unnecessary part of the sac may be removed to ensure a tidy repair.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The sac must be dissected up to the opening in the transversalis fascia. For indirect hernias, this entails a full exposure of the deep inguinal ring. All around the deep ring, the hernia sac should be meticulously dissected and detached from any attachment to the transversalis fascia. The sac can then be treated in various ways. At the deep ring, it might be twisted, transfixed, and ligated. The protruding end is then removed.

Round ligament

of the Uterus

Subcutaneous fat

Indirect hernia sac

(containing fat or bowel)

Inguinal ligament

Internal oblique muscle

Transversalis fascia

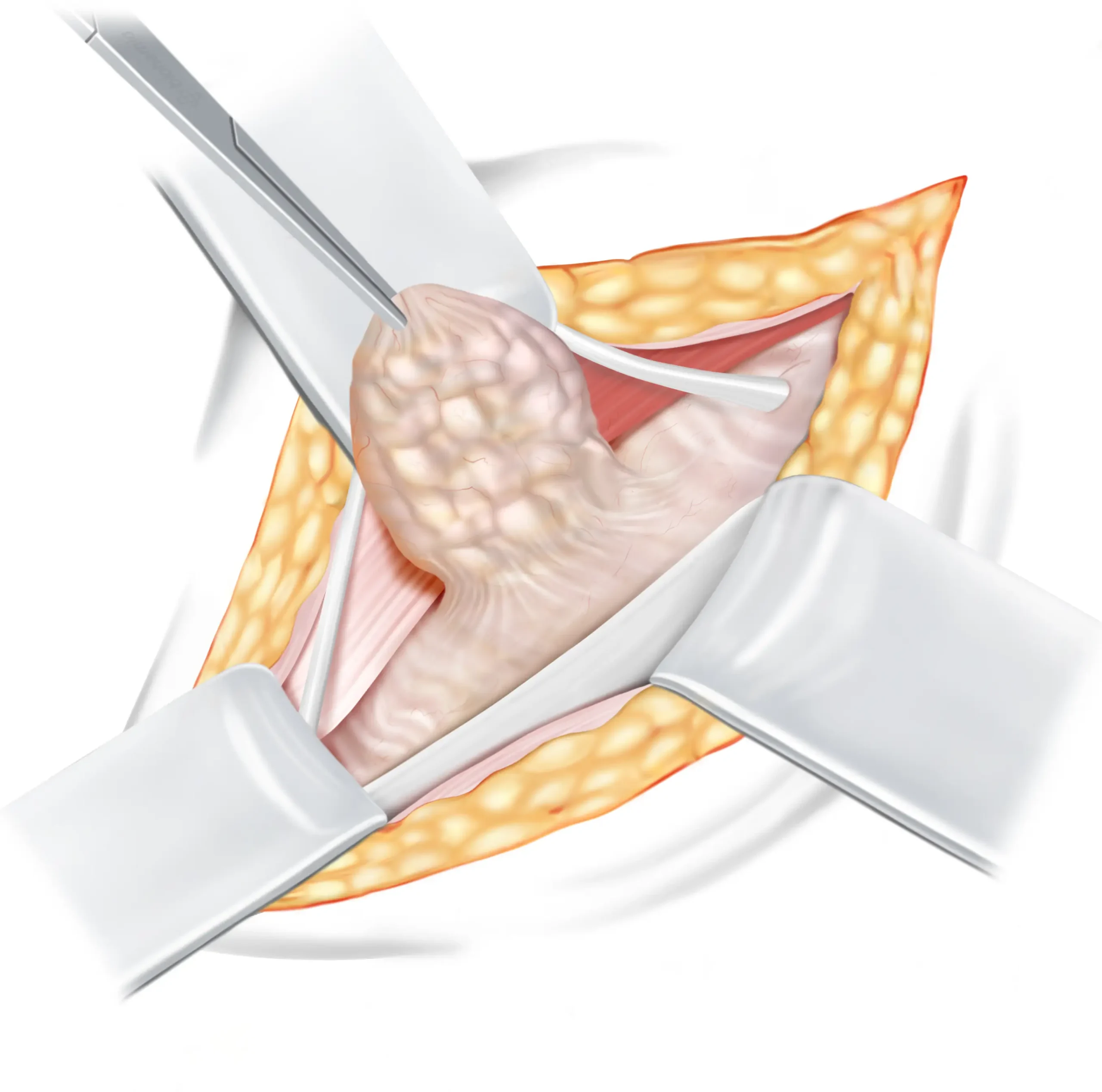

Direct hernia sac

A direct hernia is a bulge that emerges directly through a weakened inguinal floor. In a direct hernia, the hernia sac ↓ typically doesn’t need to be opened. If the sac is large in size, it should be reduced, and the base secured with a purse-string suture.

Round ligament

of the Uterus

Subcutaneous fat

Direct hernia sac

(containing fat or bowel)

Inguinal ligament

Internal oblique muscle

Round ligament

of the uterus

Subcutaneous fat

Upper portion of external

oblique aponeurosis (EOA)

Inguinal ligament

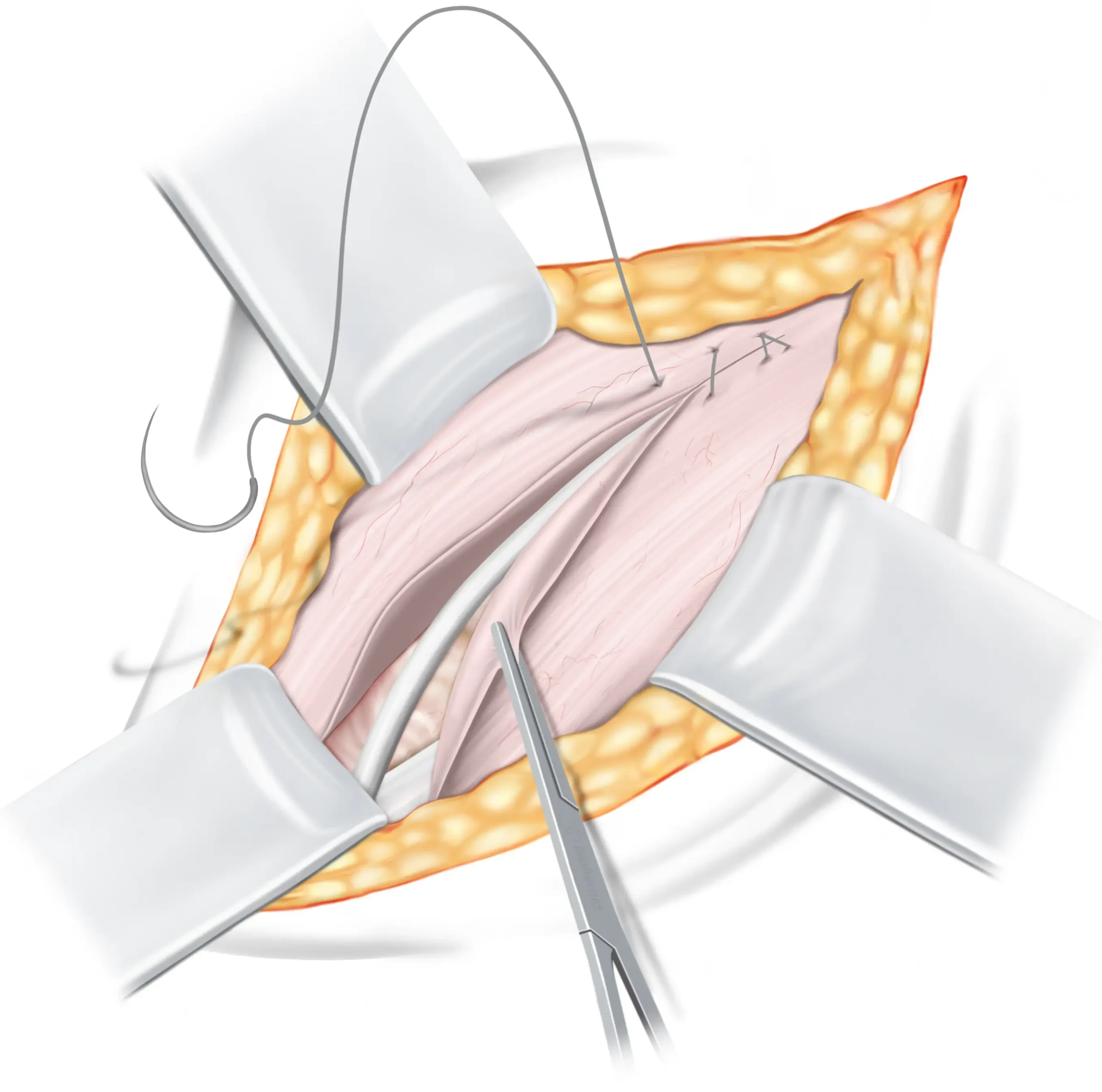

Covering the inguinal floor

With the hernia sac successfully reduced, we can proceed with the start of the Desarda repair. This involves creating a tissue flap to cover the inguinal floor, effectively preventing the recurrence of both indirect and direct hernias, similar to the way a plastic mesh does. The initial step is to carefully suture the upper portion of the external oblique aponeurosis (EOA) to the inguinal ligament. It is crucial to exercise caution during this process, ensuring that the sutures are not excessively tight to safeguard the proper functioning of the round ligament.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The upper leaf of the EOA is sutured to the inguinal ligament using continous sutures.

Round ligament

of the uterus

Subcutaneous fat

Inguinal ligament

External oblique aponeurosis (EOA)

Creating a flap

During this step, a small piece of tissue, approximately 1-2cm in size, is carefully made by making a gentle cut that runs alongside the inguinal ligament. This cut is extended towards the middle until it reaches a bone called the pubic symphysis and outwardly by about 2-3cm beyond the internal ring.

It is important to note that the attachment and connection of the external oblique aponeurosis (EOA) are kept intact and undisturbed. This means that the original tissue remains connected without any harm or disruption.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

A strip measuring approximately 1-2cm is carefully created by making an incision in the EOA, parallel to the inguinal ligament. This incision is then extended towards the middle up to the pubic symphysis and an additional 2-3cm past the internal ring. The initial external oblique muscle’s connection and its consistent flow with the strip remain intact and preserved.

Round ligament

of the uterus

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

Internal oblique muscle

Iliohypogastric nerve

Inguinal ligament

Newly created strip

covering the inguinal floor

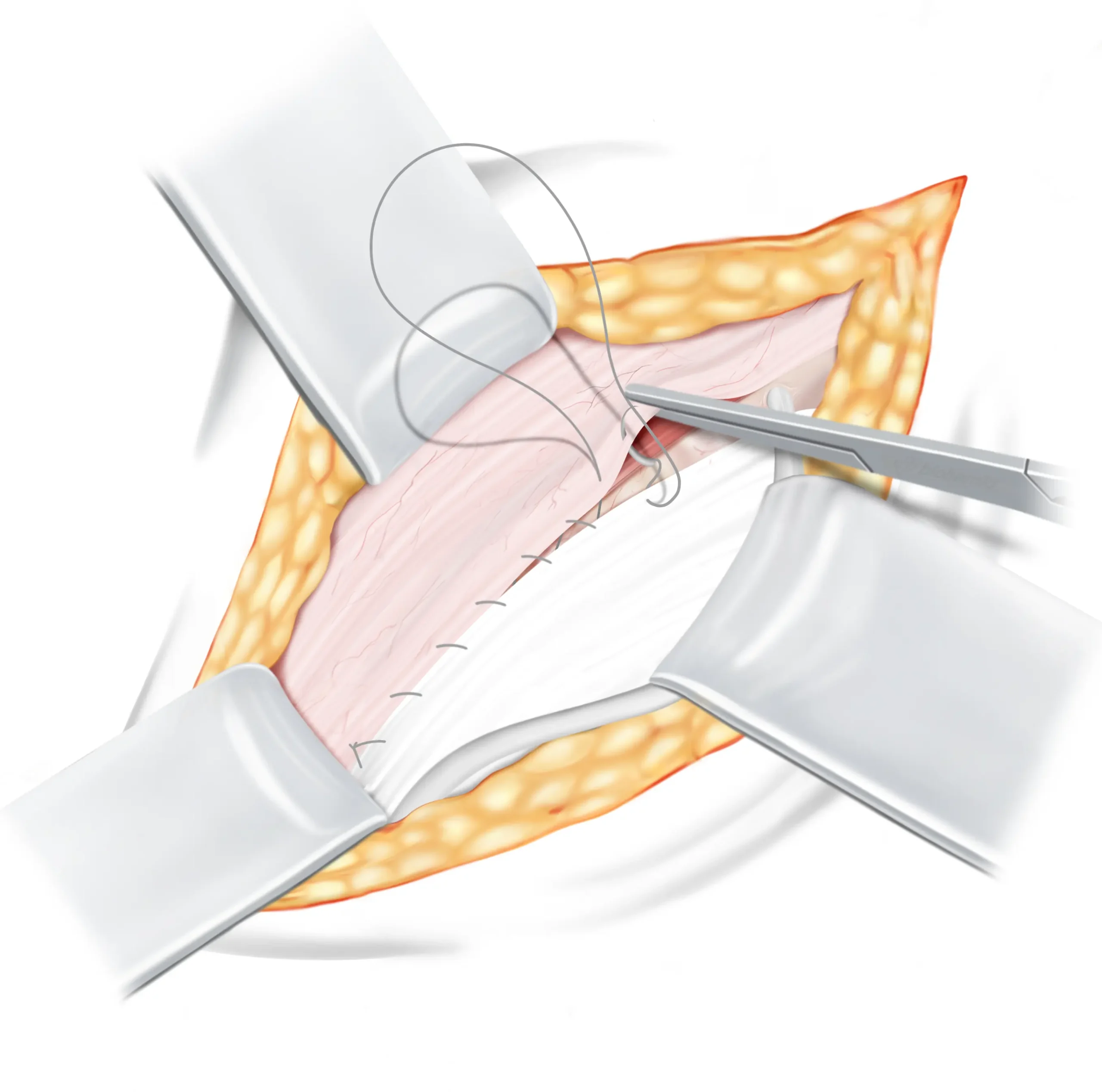

Creating a new inguinal floor

Once the strip is prepared, we’ll proceed with the Desarda repair’s final step. This involves attaching the strip to the internal oblique muscle, forming a new inguinal floor and effectively preventing both a direct and indirect inguinal hernia. Before starting the sutures, our surgeons carefully locate the iliohypogastric nerve, often concealed beneath the EOA’s upper portion, to ensure it’s not caught in the suture line.

DETAILED EXPLANATION

The top edge of the strip is attached to the internal oblique muscle using continuous sutures. The initial suture is anchored at the strip’s medial end close to the pubic symphysis and then secured to the internal oblique muscle. Successive sutures are taken near the top border of the strip, keeping as close to its edge as feasible (about 1-2 mm). This suture method proceeds along the length of the strip, extending an additional 2-3 cm beyond the internal ring. As a result, the EOA strip serves as the new posterior wall of the inguinal canal.

Round ligament

of the Uterus

Subcutaneous fat

External oblique aponeurosis

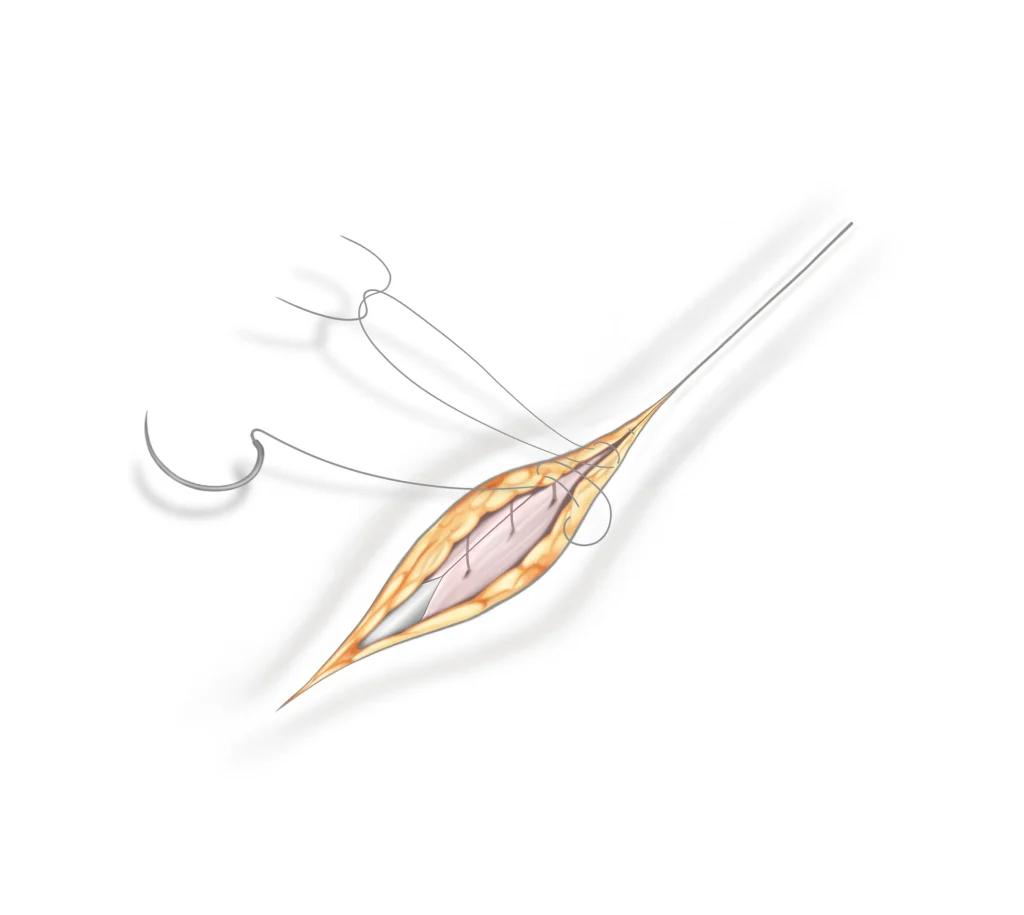

Finalising the repair

The round ligament is carefully returned to its natural position, and the inguinal canal is closed by bringing together the fascia of the external oblique muscle and securely suturing it with resorbable sutures.

Closing the skin

After the procedure, the incision is closed using sutures that the body naturally absorbs. Therefore, there is no need for you to return for suture removal, as these sutures dissolve on their own. Local anaesthetics will also be applied, which could make the area look somewhat swollen after the operation, but this is a typical response and helps reduce pain after the operation.

Wound care

In the final steps, medical glue and Steri-Strips are applied to your wound. These strips aid in holding the wound’s edges together, minimising potential scarring during the healing process. You can safely remove the strips after one week.

DISCLAIMER

The illustrations displayed on this page have been adjusted in size—some enlarged and others reduced—to enhance understanding. They are intended to provide a simplified explanation of the operation technique and do not accurately portray the complex nature of human anatomy, nor do they convey the intricate challenges encountered during actual surgical procedures. Within the human body, everything is interlinked, making the identification of tissues, nerves, and blood vessels more challenging than what is suggested by the illustrations. Consequently, considerable experience and surgical skill are essential to accurately and effectively perform the operation technique illustrated.

Frequently asked questions

1. What makes the Desarda repair different from other hernia treatments?

The Desarda repair stands out among hernia treatment techniques for its use of a physiologically dynamic strip of the patient’s own connective tissue, taken from the external oblique aponeurosis, to reinforce the weakened area. This natural tissue is beneficial as it is inherently strong and flexible, crucial characteristics that minimize the risk of complications commonly associated with synthetic materials, such as infection or rejection.

It’s important to note that the Desarda repair, while innovative in its avoidance of mesh, is the least scientifically proven method among our hernia repair techniques. The long-term outcomes and broader efficacy studies are less established compared to other methods like the Shouldice repair ↗. If you are considering this option you should discuss the potential benefits and limitations thoroughly with our surgeon to make an informed decision.

2. Is the Desarda repair suitable for everyone?

The effectiveness of the Desarda repair relies heavily on the quality of the connective tissue in your groin area, which must be strong and flexible enough to support the repair. Due to their anatomy and typically stronger connective tissue in the groin, women are often more suitable candidates for the Desarda repair.

Generally, this technique is more suitable for younger patients, as they tend to have healthier, more resilient tissue that can better adapt and integrate into the repair structure, providing a reliable and durable solution with minimal risk of recurrence. Older patients, or those whose tissue quality has diminished due to factors like smoking, excessive drinking, or certain health conditions, might not achieve optimal results with this technique and may need to consider other repair options that do not depend as heavily on the condition of connective tissues. In those cases, the Shouldice repair ↗ offers a better alternative.

3. How long is the recovery period after a Desarda repair?

Recovery times can vary, but most patients can resume light activities within a few hours after surgery. Full recovery, including returning to strenuous activities or heavy lifting, usually takes about 4 to 6 weeks. Individual recovery may vary, and it’s important to follow the specific guidance provided by your surgeon.

4. Are any nerves cut during the operation?

In the inguinal area, there are three nerves: the ilioinguinal nerve, the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve, and the iliohypogastric nerve. During our inguinal hernia operations, none of these nerves are cut. We take the utmost care to preserve these nerves, ensuring the best possible outcomes for our patients. This careful approach minimises the risk of nerve-related complications and contributes to a smoother recovery.

5. Is the round ligament kept intact during the Desarda repair?

Yes, in the Desarda repair, the round ligament is preserved. Our approach prioritises preserving as much of the natural tissues as possible. The round ligament plays a crucial role in providing support and stability to the pelvic region. We believe that maintaining the integrity of the round ligament offers more benefits than the potential advantages of cutting it.

6. What is the difference between a direct and indirect hernia?

A direct hernia occurs due to a weakness in the abdominal wall, commonly seen in older individuals. An indirect hernia, however, protrudes through the inguinal canal following the spermatic cord, and is often a condition present from birth. In terms of prevalence, indirect hernias are more common than direct hernias. However, since the Shouldice repair is designed to address both direct and indirect hernias at the same time, it’s not necessary for you to distinguish between them.

7. What is the success rate of the Desarda repair?

The Desarda repair has demonstrated excellent outcomes in clinical settings, particularly in our clinics where we have observed a lifetime risk of recurrence of 2% or less—this translates to a success rate of over 98%.

The success of this repair technique is notably high in a specific group of patients—healthy, younger individuals. If you are considering the Desarda repair, it’s important to discuss these outcomes with our surgeons to understand how this success rate may apply to your specific situation and health profile.

8. Can I return to my regular activities and exercise routine post-Desarda repair?

Yes, you can return to your regular activities and exercise routines after a full recovery from the Desarda repair. However it’s important to gradually reintroduce activities, following the guidance of our surgeon and also by listening to your body. Light exercises can be resumed within a week, but strenuous activities should be approached with caution until full recovery is confirmed. After full recovery, there are no limitations in terms of the load and intensity of activities and exercise. Patients can confidently return to their previous levels of activity and even seek to improve further, without restrictions.

9. Does the Desarda repair cause tension in the groin?

The idea of a “tension-free” repair is more of a marketing term used by various hernia repair methods to highlight their approach. However, a certain degree of tension is inherent in the nature of hernia repairs. This includes the Shouldice repair, as well as other natural-tissue and mesh-based techniques.

When we talk about repairing a hernia, what we’re essentially doing is bringing tissues together to mend a tear or weakness in the abdominal wall. This process naturally introduces some initial tension to the area as the muscles and tissues are aligned for healing. However, this sensation is typically mild and temporary. The human body is remarkably adaptable. Just like muscles gradually stretch and strengthen in response to exercise, the tissues in the abdominal area adjust and heal post-repair, leading to a reduction in initial tension through a process known as muscular adaptation.

This healing journey mirrors natural body changes, similar to those experienced by weight lifters as their muscles adapt to lifting heavy weights, or the incredible adjustments a woman’s body makes during pregnancy. So, while there may be some initial, minor tension felt with the Shouldice repair, it’s a part of the natural healing process, easing off as your body adapts and recovers.

Terminology

Learn more about the hernia terms used on this page, in our simple, easy-to-understand glossary.

External oblique aponeurosis

The external oblique aponeurosis functions as a connecting tissue that links the external oblique muscle to the bones in the abdominal region (the lower ribs and the pelvis). Think of it as a robust sheet that fastens the muscle to its surroundings. This connection offers stability and support to the muscle, enhancing the overall strength and functionality of your abdominal area. While its main role is in muscle attachment, it also contributes to the structural integrity of the abdominal wall.

The inguinal canal

The inguinal canal is a canal located in the lower abdomen, next to the groin. It acts as a pathway for structures like blood vessels and the spermatic cord to pass through. This canal plays an important role in male anatomy and sexual functionality.

The internal ring

Consider the internal ring to be a sort of gateway in the lower abdomen, near the groin. It’s a natural opening in the abdominal wall. This opening allows blood vessels and the spermatic cord to travel between your inner abdomen and the groin area. The internal ring, similar to how a door allows you to go between rooms, allows various parts of the body to move around where they need to be. It’s a natural component of how our bodies are constructed.

Hernia sac

A hernia sac is a delicate, pouch-like structure that develops when a section of an organ or fatty tissue pushes through a vulnerable area or gap in the surrounding muscle or connecting tissue. Think of it as a small pocket that accommodates the bulging tissue. The size and location of hernia sacs can differ depending on the type of hernia.

The inguinal ligament

Imagine the inguinal ligament as a kind of strong, flexible band that runs from the front of your hip bone to the pubic bone. It’s like a support belt for your lower abdomen and groin area. This ligament helps hold things in place and provides stability to the region. Just like how a belt supports your trousers, the inguinal ligament supports the structures in your lower belly, making sure everything stays where it should be.

Internal oblique muscle

The internal oblique is one of the three layers of muscles that make up your abdominal wall. In the inguinal area, the internal oblique muscle is sandwiched between the external oblique muscle and the transverse abdominis muscle. Think of the internal oblique muscle as a layer of muscle in your abdomen, just beneath your skin and the surface muscles. It’s like a hidden layer that adds strength and support to your belly. This muscle helps you twist, bend, and move your torso.

The round ligament of the Uterus

The round ligament is a strong connective tissue that supports and stabilises the uterus and stretches from each side of your uterus to the groin area. You can think of it almost like the drawstrings of a hoodie, helping to maintain the position of the uterus by connecting it to the front of your pelvic area. Just as drawstrings help keep a hoodie snug and properly fitted, the round ligaments help keep the uterus aligned and stable as it grows during pregnancy, ensuring comfort and support as your body changes.

Resorbable sutures

Resorbable sutures are designed to have a controlled rate of breakdown in your body. This means that over time, the sutures gradually dissolve and get absorbed by your body. They’re made from a substance that breaks down through a natural process called hydrolysis.

Further reading

Explore our curated selection of scientific literature for a deeper understanding of the Desarda repair.

- Köckerling F, Koch A, Lorenz R. Groin Hernias in Women-A Review of the Literature. Front Surg. 2019 Feb 11;6:4. ↗

- Schumpelick V. Does every hernia demand a mesh repair? A critical review. Hernia. 2001 Mar;5(1):5-8. ↗

- Pivo S, Huynh D, Oh C, Towfigh S. Sex-based differences in inguinal hernia factors. Surg Endosc. 2023 Nov;37(11):8841-8845. ↗

- Koch A, Lorenz R, Meyer F, Weyhe D. Hernia repair at the groin—who undergoes which surgical intervention? Zentralbl Chir. 2013;138:410–7. ↗

- Thairu NM, Heather BP, Earnshaw JJ. Open inguinal hernia repair in women: is mesh necessary? Hernia. 2008 Apr;12(2):173-5; discussion 217. ↗

- Bendavid R, Howarth D. Transversalis fascia rediscovered. Surg Clin North Am. 2000 Feb;80(1):25-33. ↗

- Philipp M, Leuchter M, Lorenz R, Grambow E, Schafmayer C, Wiessner R. Quality of Life after Desarda Technique for Inguinal Hernia Repair-A Comparative Retrospective Multicenter Study of 120 Patients. J Clin Med. 2023 Jan 28;12(3):1001. ↗

- Köckerling F, Lorenz R, Hukauf M, Grau H, Jacob D, Fortelny R, Koch A. Influencing Factors on the Outcome in Female Groin Hernia Repair: A Registry-based Multivariable Analysis of 15,601 Patients. Ann Surg. 2019 Jul;270(1):1-9. ↗

- Pereira C, Varghese B. Desarda Non-mesh Technique Versus Lichtenstein Technique for the Treatment of Primary Inguinal Hernias: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus. 2022 Nov 18;14(11):e31630. ↗

- Mohamedahmed AYY, Ahmad H, Abdelmabod AAN, Sillah AK. Non-mesh Desarda Technique Versus Standard Mesh-Based Lichtenstein Technique for Inguinal Hernia Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. World J Surg. 2020 Oct;44(10):3312-3321. ↗

- Desarda M. New Technique of No Mesh Inguinal Hernia Repair. Pune, India; 2019 ↗